Before I move on from land-based cryptids, I have to pay tribute to one last, unique animal. The thylacine or Tasmanian tiger was officially declared extinct in 1986, fifty years after the last one died in captivity. But there’s a strong belief in Tasmania that the thylacine is not in fact extinct; that there may be a population, however small, still living and breeding in the remoter parts of the island.

In fact the last credible sighting occurred in 1982, when a park ranger happened to be doing a game survey. He had pulled over to the side of the road and camped for the night. Around two a.m. he shone a light out into the road, and caught what he declared was, without a doubt, a Tasmanian tiger. A healthy male, he said, four to five years old. He observed it for several minutes until it moved off into the bush.

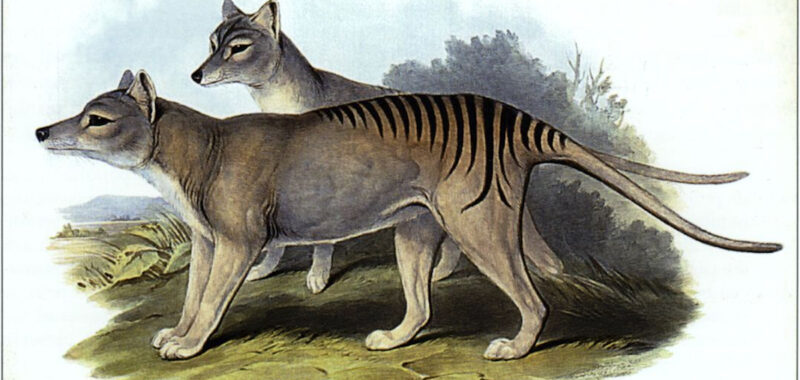

What he saw was an apex predator, a marsupial about the size of a small wolf or a medium-large dog. Its snout was long and pointed and capable of opening to ninety degrees, with a daunting array of teeth. Its ears were smallish and rounded; it had a distinctive conical hind end with a long, straight, inflexible tail. It was sandy in color, with the distinctive stripes over the back and hindquarters that gave it its name.

This was a trained observer, and he knew what he was seeing. After his report was filed, biologist Nick Mooney conducted a two-year search which yielded no results. That didn’t deter scientists and enthusiasts from continuing to search off and on through the Nineties and into the new millennium.

Both official and unofficial investigations have turned up no evidence that the thylacine survives, but the sightings continue. Occasionally a searcher finds tracks that might or might not be thylacine tracks. Sometimes there’s a photo or video, but none so far of high enough quality to state categorically that yes, this is a thylacine.

Youtube has a nice collection of influencers and wildlife enthusiasts taking to the trail and recording their adventures. They do their homework; they sum up the history and weigh in on the likelihood that somewhere, deep in the bush, Tasmania’s iconic predator is still alive. They never find anything, but what they manage to do is show the world how beautiful Tasmania is, and how much of it is still wild.

Earlier this year, 60 Minutes got into the game with a segment that first aired in April and then repeated in June. They reported on the tragedy of the species’ extinction and the persistence of belief that it’s still out there. They checked in with Nick Mooney himself along with a number of other experts.

They also touched base with Andrew Pask, a researcher in Australia who is so devoted to the idea of the thylacine that he’s trying to bring it back to life through a process called de-extinction. He’s doing this not through cloning (though some sources are calling it that) but by tweaking the DNA of a living relative: the fat-tailed dunnart. This is the Down Under version of the grasshopper mouse, a tiny, ferocious predator that’s close enough genetically that Pask believes he can edit its DNA to recreate the thylacine.

Not everyone believes Pask can do it. Fellow biologist Chris Helgen points out that gene editing is a process of trial and error. You tweak a few dunnart genes, get something a little bigger. Tweak a few more, size it up a tad. Another tweak, you get some stripes. It’s a long process, he says: 1001 steps to get something that looks like a thylacine, but it’s really not.

So why do it? he asks. It’s an attempt to redeem ourselves for driving this animal to extinction. We feel the guilt; we mourn the loss. We try, in our bumbling way, to make up for our terrible mistake by bringing it back.

In Helgen’s view, this is a waste of resources. We should focus on endangered species, on animals that are still alive, that can still be saved. Let’s keep what we’ve got, and not try to bring back what we’ve lost.

I can imagine what he’s saying about the scientists who are trying to bring back the mammoth. Or the ones who talk about retconning chickens and ending up with dinosaurs.

I tend to agree with Helgen. It’s tragic that the thylacine is lost; it did not have to be, if humans had known or cared about preserving an essential part of the native ecology. But there’s enough to do to keep what we still have, while also keeping the climate from collapsing.

And if there really are thylacines out there, somehow? If the whispers are true, that locals are keeping their lairs and habitats secret, to keep them from being overrun? Good for them. I hope they survive.