A Quiet Place: Day One. Alien: Romulus. The First Omen. Immaculate.

These films have thrilled general audiences and fright flick fans alike, ranking among the highest grossing movies of 2024. The cynical among us might contend that these movies do so well because of their political messaging. Those four entries alone mix their scares with narratives that reflect real-world concerns about women’s autonomy over their bodies, the exploitation of workers’ rights, our increasingly divisive and dehumanizing political landscape, and more.

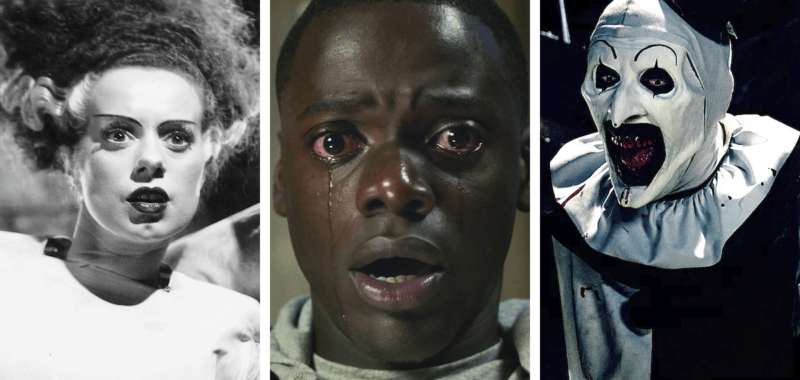

More and more, scary movies fall into what some call “elevated horror,” films intended not just to shock audiences, but to also make them think. The concept exploded back in 2015, when Jordan Peele’s debut feature Get Out dominated the box office and was nominated for the Best Picture Oscar. A frightening parable about the insidiousness of benevolent racism, Get Out changed the way some people thought about horror, elevating the genre from a lowbrow distraction that appeals to viewers’ baser natures to an art form that speaks on the pressing issues of our day.

No one would deny the power of Get Out, nor Peele’s deft direction and unique vision. But to act like the film fundamentally changed horror misunderstands the genre. Horror has always been political, and it always will be.

All Monsters Have Meaning

The Bride of Frankenstein seems, at a glance, about as apolitical as a movie can get. A classic, yes. But a 1935 movie based on an 1818 novel, about the rivalry between mad scientists Baron Henry Frankenstein (Colin Clive) and Doctor Pretorius (Ernest Thesiger), who strive to make a mate for the Monster (Boris Karloff), The Bride of Frankenstein seems designed for pure escapism, a mix of scares, humor, and romance.

However, it’s impossible to watch The Bride of Frankenstein without noticing that it’s about men trying to construct the perfect woman, for the pleasure of another man (well, a male-presenting monster). Furthermore, the frame narrative—in which the Bride’s actor Elsa Lanchester also portrays Frankenstein author Mary Wollstonecraft Shelley—features a woman pressed into telling a story at the behest of male writers (Gavin Gordon playing Lord Byron and Douglas Walton portraying Mary’s husband Percy Bysshe Shelley). Mary undercuts the masculine claims to creative genius with a story about a woman who rejects even the men who made her.

If a classic film based on Victorian literature seems too obvious, take Friday the 13th instead. By the admission of everyone involved, Friday the 13th was created to take advantage of Halloween’s box office success, throwing in more kills and bared skin to tease viewers, ensuring the maximum box office return on their microscopic budget.

Friday the 13th makes no claims to originality, let alone basic good taste. Nor does it even pretend to say something about human nature. And yet, Friday the 13th ends up uncovering fears that parents felt about the safety of their children and anxieties over the perceived sexual permissiveness and impropriety of the next generation of adults. In Friday the 13th, the penalty for this self-involved hedonism takes the grim form of Jason Voorhees (well, Jason’s mother Pamela Voorhees, but you get it).

If the decades have washed away Friday the 13th’s poor reputation, changing trash into treasure as hindsight always does, we can look at the Terrifier series. The brainchild of Damien Leone, the first Terrifier released in 2016, the second in 2022, and the third is set to release later this year.

Against the aspirations of elevated horror, the Terrifier series seems to exist just to shock. Terrifier and Terrifier 2 have the barest of narratives, and just focus on Art the Clown (David Howard Thornton), who pantomimes for victims before mutilating them in stomach-churning fashion. Leone languishes in the cruelty of his set-pieces, at once showing off the movies’ (impressive, by any measure) practical special effects while also daring the audience to look away. The Terrifier movies celebrate their bad taste, transgressing every boundary with glee.

And even that is political. No one can watch the way Art dismembers female bodies in Terrifier without thinking about the arguments about the way advertisers and onlookers reduce women to their individual parts. The stand-out dinner table sequence in Terrifier 2 packs a punch because of the way it transforms a conventional suburban home into a house of horrors.

No one can escape the political in horror. Not Frankenstein, not Jason, not Art the Clown. No one.

Founding Fears

Horror is always political because fears and anxieties do not exist in a vacuum. Filmmakers need some sort of common ground or larger social context to draw on in order to frighten viewers. Sure, a director can just have a creature jump onto the scream and shout “Boo!” and those types of jump scares have their place, but those moments only startle viewers. They don’t truly scare them.

To scare the members of the audience, a film has to invoke something that the audience doesn’t want to see, or even think about—something the viewer wants to forget. The horror has to transform the audience’s perception of a safe place or turn the familiar into the uncanny, the strange.

That’s why David Lynch’s work, even if not always categorized as horror, can be simultaneously so scary and so mundane. When he holds his camera on a ceiling fan in the pilot to Twin Peaks, Lynch takes the most commonplace thing in the world and compels viewers to watch it for longer than anyone otherwise would. Add in a rumble on the soundtrack and blurring effect from a slowing of the film, and the ceiling fan becomes odd, unnerving. It becomes a sign of something very wrong in the Palmer house.

The social quality of horror means that scary movies always have a deeper meaning, even if the creators didn’t intend it. Godzilla remains such a powerful metaphor about the scars of atomic bombs not because the 1954 movie constantly forces us to look for the underlying connections, but because it functions so well as a story about a giant lizard stomping Tokyo. It doesn’t need to scream about its larger meaning—atomic energy and Japanese cities in shambles mean inherently more to us, collectively, than just kaiju collateral damage. They evoke, inescapably, the wastes of Nagasaki and Hiroshima.

With that in mind, Wes Craven (or better yet, someone helming a later, lesser sequel, such as Renny Harlin or Rachel Talalay) can make Freddy Kruger because a dream demon with razor claws is without question scary, but every Nightmare on Elm Street film highlights parents’ powerlessness, even in the suburbs. The blood-soaked Saw movies might seem like nothing more than Grand Guignol excesses with better effects, but their emphasis on torture from a self-righteous figure echoes the policies of the United States during the War on Terror.

Even the most straightforward horror film is a product of the time, and the societal context, in which it is created. And anything that reflects the cultural moment and the prevailing ideologies and frictions playing out within a society is, by definition, political on some level.

Instead of getting annoyed about the political aspect of horror movies, fans should learn to embrace the deeper means as a feature of their favorite genre. As just this brief survey shows, everything from classics to high-brow masterpieces to the trashiest schlockfests have political aspects, and those aspects don’t diminish the reputation, the class, or the gore. In fact, the political aspects enhance the good stuff.

Sure, some filmmakers do better than others at combining scares with social commentary. Ham-fisted films such as Smile or the 2022 Danish version of Speak No Evil seem to underline every shocking moment with a blinking sign that nudges the audience, asking “Get it?!” Yet, clumsy creators have never diminished the talented ones. Which brings us back to Jordan Peele. Although Peele certainly didn’t invent the idea of political horror with Get Out, he did show that he is really, really good at it. Peele has followed Get Out with two more movies, just as audacious and skillful as Get Out. In fact, some fans (read: this writer) think that Us (2019), with its riff on doppelgängers and social inequality, and Nope (2023), a big-budget exploration of spectacle, media, exploitation, and erasure are even better than Get Out… and Get Out is a five-star film.

Yet, as great as Peele is, movie makers don’t have to be just as skillful or thoughtful or fun to be political. They just have to want to scare us. The politics will always be there, to complicate or deepen the narrative… and frankly, politics are scary enough all on their own right now.