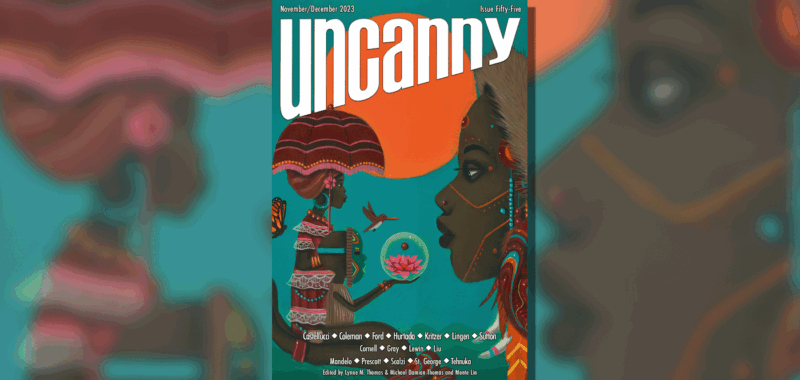

Welcome back to Reading the Weird, in which we get girl cooties all over weird fiction, cosmic horror, and Lovecraftiana—from its historical roots through its most recent branches. This week, we celebrate National Poetry Month with Sonya Taaffe’s “Amitruq Nekya” (Strange Horizons, October 2024), Lora Gray’s “How To Haunt a Northern Lake” (Uncanny Magazine, November/December 2023), and Portia Yu’s “Little Haunted House” (Strange Horizons, January 2025). Spoilers ahead!

Unlike Coleridge’s long narrative poem, “Christabel,” these poems defy summarizing. To paraphrase Gollum: “Read them! Read them! They are short, precious, they are tasty, they are munchably crunchable!” Especially if you print them out first and toast them lightly over an open flame.

What’s Cyclopean: Taaffe’s glaciers are “calving to myth and memory.” Yu’s door “looks like a tooth” and “smells like a frog.”

The Degenerate Dutch: Taaffe’s Northwest Passage explorers are the last pieces of an empire that never thought it would lose the high ground.

Madness Takes Its Toll: Gray’s ghost must consider what sort of spirit it would become haunting “a bungalow, heavy with cigarette stains and unhappy marriages” or “a stiletto, forgotten beside a bus stop, and desperate for companionship.” These make eternally mourning a lost lake sound like a pretty good deal.

Ruthanna’s Commentary

Trying to pick recent poetry for the column, I read a batch of recommendations and let shared themes float to the top. (Like algae on a northern lake?) These ones felt like a set: hauntings, and the ecosystems of which they’re a part.

I’ve been reading Robin Wall Kimmerer’s books on nature’s gift economies, and humans as an inextricable part of them. This is probably about as far from weird fiction as you can get, except that it, too, questions where we set the boundaries of self, species, civilization. Cosmic horror comes from a tradition in which human triviality is a terrifying violation of sanity-protecting assumptions. This is because cosmic horror comes from a tradition in which some people—some parts of the universe—are important and some are trivial. The trivial parts can be ignored when worrying about the effects of our actions. They can be used, or used up, without thinking about anything other than how that use provides value or annoyance to the important people. The Yith are scary because they’re the British Empire writ large, and don’t consider anglo imperials any more important or interesting than anything else in their records. The Outer Ones are scary because they suggest that maybe everyone being equal might be okay. It might even be fun – but think of all the power you’d lose in accepting that shared personhood.

Poetry Month, Ruthanna. Talk about the poems.

I’m getting there. If humans don’t stand out among the living, if we’re just another inextricable part of nature, then what if we don’t stand out among the dead either? In all of these poems, the human spirits have to find their place in an ecological niche. Often, that niche is itself in the process of translating from living world into haunt: an evaporating lake, a melting glacier.

Taaffe’s would-be Victorian discoverers never considered such a thing in life. Hubristic explorers, seeking the Northwest Passage for trade and international dominance, they find themselves now released from the ice that dominated them, like carbon from permafrost. Which suggests they’ve gained no wisdom from their deaths, but are still a force for destruction, born of the destruction they contributed to. They’re “irreducible” skeletal remnants of empire. But we, the living, can perhaps still learn from the “liquid lesson they met hard as a mirror” before the “high ground” melts entirely out from under us.

Gray’s second-person ghost integrates that lesson rather precisely. Haunting, they explain, is a decision about sustainability, about what system you’ll be part of in death. It’s a decision about caring. You might be invasive, or you might be an “immigrant species” that contributes to what’s already there. The important thing is not to assume, but to examine and judge your impacts on everything in the lake. Then there’s the need for an invitation – another part of Kimmerer’s interspecies relationships, that requirement for conversation and reciprocity, as much with a ghost ship as with a stand of sweetgrass. And finally there’s the long-term view: the lake’s own mortality, and the choice to love it anyway, giving up your living boundaries in exchange for belonging.

Gray urges you to consider your haunting options, and Yu’s tiny house seems a natural outgrowth of that consideration. It’s not so obvious an ecology as the other two, and yet it’s so clearly a niche. It’s a question of fitting – of body bigger than mind, “the way it was supposed to be.” The miniature house is a place of details, of paring down to personal meaning: “a window, a rose bush, a fish, a belly, a thorn.” We don’t know what these mean, but we know they mean something to the ghost. And that in choosing this tiny, perfect place, it becomes able to encompass “my sky and my sea.” It becomes an ecology because it’s the right fit.

Anne’s Commentary

“Amitruq Nekyia” by Sonia Taaffe — Reading Taaffe’s poem, or rather, after reading it several times, I pulled a John Livingston Lowes. You remember that guy, right? Always sat in the front of the class, straining to make his perpetually raised hand show above the monster pile of books stacked on his desk? Earned critical immortality with The Road to Xanadu (1927), his exhaustive study of the sources and influences of Coleridge’s “Rime of the Ancient Mariner” and “Kubla Khan”? Yeah, him. Made a great rum punch, too, or was that someone else?

Anyway. The second line of “Amitruq Nekyia”—“those specters thawing out of the Northwest Passage”—made me think of the ill-fated Franklin Expedition of 1845 and, more specifically, of Dan Simmons’s 2007 novel, The Terror, and its 2018 TV adaptation, both of which have scared me into a preemptive cancelling of all my sailing trips into the great Arctic whiteness. With that impression in mind, I started looking up the bits of the poem I didn’t quite (or at all) understand. The title, naturally, came first. I searched for both words together, which led me in a tight circle back to the poem itself. Searching for the words separately did the trick. “Amitruq” is Inuktitut, an Inuit language spoken in Eastern Canada; it refers to the Arctic waterway also called Terror Bay, where the wreck of the Franklin Expedition ship, the Terror, was discovered in 2016. “Nekyia” is Ancient Greek for a ritual to summon and question the dead, usually about the future.

Its parts united, the title refers to an attempt to perform necromancy on the long-frozen corpses of Franklin Expedition crew members. The “Larsen C” that’s silting their “famished spoor of boots and buttons” is an Antarctic ice shelf with a history of massive iceberg calving events. While the icebergs themselves don’t directly raise sea level, accelerated outflow from glaciers behind the lost shelf “barricades” can do so, with global impact even unto the Arctic regions.

The “sundogs” following like hunting hounds on the heel of the Expedition’s “ever shifting north” are atmospheric phenomena caused by the refraction of sunlight through ice crystals in high-altitude clouds. They create bright spots on either side of the sun, giving the impression of three stars rather than one. Some consider sundogs a harbinger of good luck, others of bad weather or increasing cold. Capt. Francis Crozier, commander of the Terror, sees sundogs early in the Expedition’s travels; he apparently looks on them as ill omens.

“Brash ice” works as an image of unruly sailing or trekking conditions, but it’s also a real thing: The smaller fragments of floating ice left by the breakup of floes or pack ice.

The phrase that gave me the hardest chase was “soft lead oracles.” “Lead oracles” alone led me into a brash ice of tech sites concerning the Oracle analytic function LEAD. “Soft lead” wandered into journalism sites that differentiated between the “soft” article lead-ins that are more descriptive and narrative in form and the “hard” article lead-ins that immediately reveal the main point of the story in a concise and factual manner. But “soft lead” also refers to the metal. One theory about the deterioration of Franklin Expedition crew members is that they were being poisoned by defective lead soldering in their canned food supply or water storage vessels. That definition makes sense of “soft lead oracles,” at last! Among many other dire conditions, high lead levels in the human body can cause hallucinations, making false “oracles” of those thus afflicted.

“White drill” still has me puzzled. Search that if you want to be regaled with sexy ads for power tools. Alternatively, “white drill” might refer to Caucasian artists in the Chicago-based subgenre of hip-hop known as drill music. “Red ink,” I got that. It refers to financial losses or debts, to which empires however expansive are subject.

“Kelp-clappered” is just a gorgeous way to describe bells that must finally toll out on the ice pack.

Overall, Taaffe wonders what would-be necromancers of dead and disappointed Arctic explorers could want to ask the spirits they raise. Would they look for insight into “cold equations” of fuel and food and ice crush over time for which John Franklin failed to find the right answer? Reflections on the costs of empire-building? Intimate details of the stranded explorers’ ordeals?

Or what vision of the world yet to come can the explorer-spirits describe that would be news to us? Maybe centuries of lying in the ice, of listening to its quickening trickles and convulsions into water, have informed them of a fate they could only have longed for in the last months of their lives: A world growing warmer, warmer, hot.

Haven’t we only to unstopper our own mouths and sink into the rising damp of our own high grounds to learn those secrets?

“How to Haunt a Northern Lake” by Lora Gray — If you’re looking for a place to live, you have plenty of books and articles and blogs and podcasts to consult, tons of houses for sale and apartments to rent online, scads of hungry realtors to hire. If you’re looking for a place to eternally rest after you die, you can prepurchase cemetery lots, check out columbariums and urns from the utilitarian to the fabulous, maybe pick out the garden you want your composted remains to nourish.

But what if you’re looking for a more active afterlife? Unless you can find a friendly vampire or luck into a zombie apocalypse, haunting is the obvious answer. Some people think that you can opt for a free-range ghostliness, but sorry Charlie, the job description of a ghost is to haunt something, and to haunt means to hang around one place or person or object. Say there’s nobody you love or hate enough to want to spend your death with them. Say you’d get bored during the long intervals haunted objects may have to lie around museums, libraries, book or junk shops, attics or basements or cluttered drawers, waiting for the next hapless possessor to curse.

Then haunting a place may be the perfect choice for you! Contrary to popular belief, ghosts don’t usually haunt cemeteries or other remains-depositories—those places are for dead folk who want to rest eternally, damn it, and they do not appreciate intrusion by noisy, angsty, always on the float spirits. Popular haunting sites include the deceased’s own home (last or past) or place of violent death or beloved recreational venue. Scenic areas without specific emotional attachments are increasingly in demand, and so Lora Gray’s PSP (Public Service Poem) is timely indeed.

They succinctly yet evocatively lay out the basic how-tos of selecting such a haunting site:

Number One: Life can find a way to annoy you even after you’re dead. So consider what living things may be sharing your space. If, in your own life, you disliked murky or algae-choked water, fish, or midges, you may not like them when dead. The opposite also holds: You loved murk, algae, fish, midges! Go for that lake, then.

Number Two: Specterologists agree that at least fifty percent of all ghosts who’ve ever haunted have persisted to this day. That means most sites on the planet are already crowded. Human ghosts aren’t the only problem. Other life forms have left spirits or at least physical imprints. Make sure there’s a necro-ecological niche left for you and that you can likely get along with your dead neighbors.

Number Three: If you can get an invitation to join haunters already resident on the site you’re considering, that could be an optimal situation. Unless they’re jerks, of course.

Number Four: Sort of water-site specific but with general applications as well. Don’t be a jerk yourself by constantly bewailing your fate like a Corpse Bride or something. Remember, ideally you’ll want to haunt a place for eternity, and drama-ghosts soon wear out their welcomes.

Number Five: Do consider your options. Maybe you’d actually prefer a nicotine-drenched bungalow or a pebble on a warmer beach to that northern lake.

Number Six: Remember, places and people and things in the living world change, whereas you’re in the game forever. Is there that ineffable something about your site that will allow you to do the Ultimate Ghost Thing and go on faithfully haunting it even if it’s physically obliterated?

Happy haunt-hunting!

“Little Haunted House” by Portia Yu — One of the most powerful metaphors for the human body is the house. Philosopher Gilbert Ryle coined the phrase “ghost in the machine” to describe the idea that the mind is a nonphysical entity inhabiting a physical corpus – or a house, which is a machine for living. A poem is often divided into stanzas; in Italian, stanza means room. That would make a poem a house. Poems have form, like houses or machines. They have an internal intangible. Call it meaning, or mind, or ghost.

As metaphors for the human body or human expression, are not all houses haunted?

Even the smallest, most condensed house or poem must have one room. As in Yu’s poem here. Outside this tiny house, at first, is an enfolding silence and stillness, but is that the mind, the ghost? Only when the silence shrinks to fit inside the tiny house can it be properly haunted, and that is death but not death, because it is not all-encompassing as was the external silence. Inside the little haunted house, the mind is smaller than the body, as it should be.

Smaller than the body, the mind may see only bits of what it saw before, on the outside, but it also sees its own sky, its own sea.

I’m just saying, streaming some consciousness here.

Join us next week for Chapters 8-14 of The Night Guest, where we hopefully get more clues to a diagnosis.