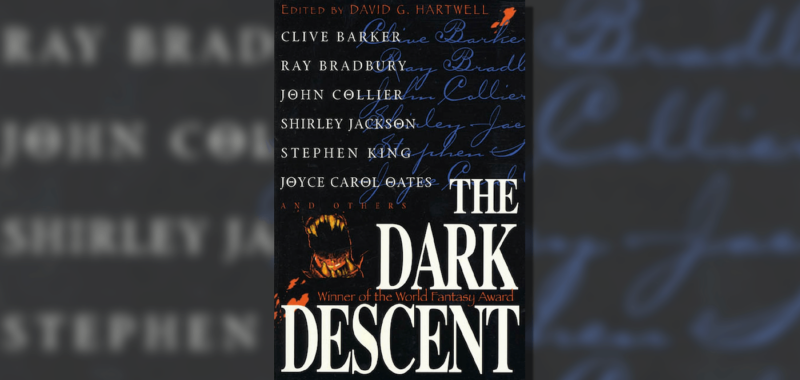

Welcome back to Dissecting The Dark Descent, where we lovingly delve into the guts of David Hartwell’s seminal 1987 anthology story by story, and in the process, explore the underpinnings of a genre we all love. For an in-depth introduction, here’s the intro post.

Tanith Lee should be synonymous with the modern gothic. Through her prolific career, Lee’s stories of love, death, rebirth, and reincarnation reshaped the boundaries of both fantasy and horror—sometimes both at the same time in works like The Secret Books of Paradys and her Flat Earth stories. “Three Days” at first seems somewhat anomalous to her work, a dark gothic story that goes against convention through the debunking of its more supernatural elements and crushing the romanticism of its central cast. Within that debunking lies not a deconstruction of the romantic and gothic but in fact a reconstruction, depicting both the perils of ungrounded fantasy and the need for a little romanticism to give one’s life hope and substance.

On the anniversary of his mother’s death, Charles Laurent invites the unnamed narrator to the home of his grotesque, controlling father to meet his family. In attendance are his artist brother Semery and his sister Honorine. Honorine is a plain but innocent young woman with a taste for the occult, one that leads her to seek a past life reading from a cadre of witches who declare the young woman to be the reincarnation of an infamous bisexual pirate and libertine who died on the day of Honorine’s birth. The idea that Honorine is a reincarnated Lucie Belmains gives her a newfound swell of confidence and spirit in the face of her abusive father and dismal living situation, but Monsieur Laurent is nothing if not vindictive, and his retaliation against his daughter-cum-prisoner drives Honorine to a single, horrifying, and destructive act.

There’s often a notable romanticism paired with the gothic, and it’s an element Lee is no stranger to in her own work. The presence of the supernatural lends things an ethereal quality, the innocent is often beautiful, the narrator is often worldly, and there’s a sense of divine order to the proceedings—the innocent will be tested, the guilty will be punished, and those who are good and moral will survive. What makes “Three Days” so disturbing is that there is no such romanticism here.

The conventions of the gothic are subverted at every point, from the aggressive plainness of its innocent central character (to counterpoint the beautiful ingenues found in more traditional works) to the clear lack of any supernatural elements. While the witches’ proclamation that Honorine is Lucie reincarnated drives much of the plot, there’s very little evidence to support the claim in the story itself. Even the “three days” mentioned in the title is a reference to a simple and pedantic argument about a small flaw in Honorine’s logic.

The horror in this story comes from the reassertion of the mundane—the bohemian protagonists and their influence on Honorine are fanciful things, shattered by Laurent’s final blow to the “house of glass” shoring up his daughter’s newfound confidence: Lucie Belmains’ death was three days after Honorine’s birth and thus she couldn’t be Lucie reincarnated. The detail that the witches got wrong (supposedly—we’ll get to that) throws aside all influence of the supernatural on the text, and Honorine’s hope is crushed by the brutal and mundane pragmatism Laurent employs when her defiance places her beyond his control.

Even Honorine’s death—a dose of rat poison taken in a dusty attic—is meant to both mirror the gothic (the attic being a place of isolation where troublesome women are shut away in gothic stories, self-poisoning being a more romanticized form of suicide) and strip it of romanticism (the image of her curled up in a dirty corner taking a fatal dose of something meant to kill vermin and pests). It’s a death that matches the tragedy and plainness of Honorine’s life, with no fanciful elements at all. It’s horrifying in how plain and sad it is.

The plainness of Honorine’s death makes it no less wrenching. Her brothers and even the narrator are all left devastated by her suicide. Rather than romanticize the death, any illusion of romantic tragedy is stripped away—Honorine dies pathetically in the attic from eating rat poison and her vile father can barely contain his glee at her passing. In absolutely wrenching detail, Lee describes how Honorine’s death tears a hole in the world around her, and in depicting the ripples from that tragic event, reveals that Honorine was in fact more remarkable than she seemed. The devastation shows the true weight and lasting impact of Honorine’s passing—her death functions as a shock to the system, waking the men in her life up to the realities of the mundane world. Semery gives up his painting and settles down to a prosiac life as a father. Charles gives up on both writing and law and becomes a hermit. While the narrator does set out to win over his lady love Annette, he does so by accepting that they are going to eke out a mundane existence far from the glamourous future he imagined for them. Honorine’s death cures each of the men of the idea that the world is a place where magic can exist.

While the romanticism is drained from the story and juxtaposed against the mundane world where monsters like Monsieur Laurent never get their comeuppance and are allowed to gleefully drive people to their death, “Three Days” is a reconstruction, not a deconstruction or subversion. Laurent is a traditional gothic villain through and through, from his unnerving presence and ability to terrorize his abused children even into adulthood to his schemes to dominate or destroy Honorine to keep her from living a life beyond his clutches. Honorine might not be an ethereal beauty, but the significance of her life and death cannot be overstated, casting her as a tragic heroine. While her death is horrifying and the story (rightfully) doesn’t portray Honorine’s suicide as romantic, it fits with the ending of a gothic tragedy, with the twisted villain winning and the heroine chooses to end her life out of despair. Lee even incorporates the three witches, who in the story’s most telling moment bring the reconstructive elements to the fore when the narrator discovers (far too late) that they were correct about Lucie’s death and possible reincarnation.

There might be very little romance to “Three Days,” but in its absence, Lee rewrites the rules of gothic horror and tragedy. She allows the reader and the narrator to focus on Honorine’s interior life rather than any kind of rare or ethereal beauty. The literal battle for Honorine’s soul between the ruthless pragmatism of Laurent and the romanticized fantasy of the witches’ prophecy rams a lance of pure existential horror through the heart of the more fanciful and romantic elements, adding a grounded and disturbing sense of reality back into the gothic work. More important than any of those, “Three Days” ultimately underlines the importance of imagination and flights of fancy, both in the disturbing lack of romanticism the work depicts and indeed in the final passages detailing how romanticism saved the narrator and might have saved Honorine from her father. We’re left with the sense that it’s important to cling to what little light one has, no matter how fanciful—that the dream you crush might be someone’s load-bearing fantasy.

And now to turn it over to you. Is Honorine’s struggle between the mundane and the fantastic, or something more? What was the load-bearing fantasy that helped you through your own dark night? And what was your first brush with Tanith Lee (the house recommends The Secret Books of Paradys, which I accidentally stole)?

And please join us in two weeks for “Good Country People” with the doyenne of southern grotesque herself, Flannery O’Connor.