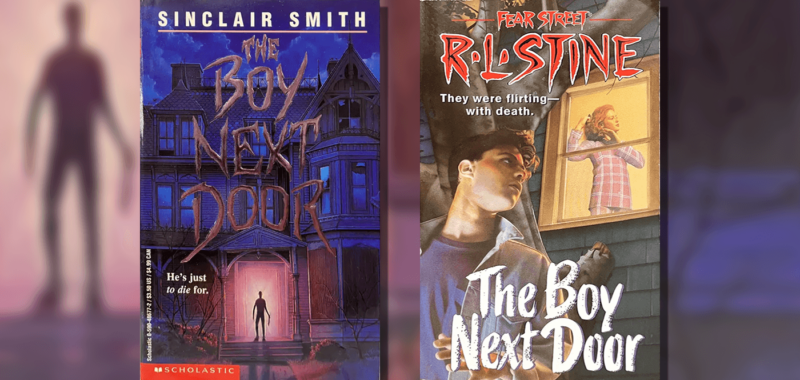

The “boy next door” trope is usually one of comfort, predictability, and reassurance. He might be someone who has been there the whole time and only gradually becomes a viable love interest, or he might be the new kid on the block. Either way, the proximity to the safety of home and family defuses some of the stress of romance and the unknown. If there’s a study date or hang out session that’s going badly, all you have to do is walk a few yards down the sidewalk and you’re back to home sweet home. If things get complicated, it’s pretty tough for him to avoid you or sneak around, and if he’s dodging your calls, you can always go knock on his door. While dating is usually one of teens’ earliest independent forays away from family, parental supervision, and the domestic space, going out with the boy next door is a kind of liminal middle ground, with home remaining in easy reach. But in Sinclair Smith’s The Boy Next Door (1995) and R.L. Stine’s Fear Street book The Boy Next Door (1996), the boys are harboring some dark secrets and the girls get more than they bargained for.

In Smith’s The Boy Next Door, Randy Bell spends a lot of time home alone: she’s being raised by a single dad, but he’s a celebrity TV handyman and is often on the road. Her best friend Alice sometimes comes over to hang out or study with her occasionally, but most of the time, Randy’s on her own in a big old house at the end of a dead-end street. The house next door has been abandoned for years and is pretty darn creepy. And things actually get creepier when someone (allegedly) moves in. Randy meets the boy next door when she’s taking out the garbage late one night and someone grabs her from behind, emitting a “throaty, menacing laugh … with all its unspoken possibilities and threats” (21). This is a straightforward “stranger danger” situation, but when Randy is finally able to turn around, she finds out the person who scared her is a cute boy who shrugs off this whole not-meet-cute as a joke, telling Randy, “I just get carried away sometimes when I’m having a good time—and I love to kid around” (24). He introduces himself as Julian Dax, Randy begrudgingly excuses his bad behavior, and things only get worse from there.

After befriending Julian, Randy starts making big changes in her life and everything basically falls apart: she quits the cheerleading squad and breaks up with her boyfriend Ted, who might not be a catch, but definitely doesn’t go around assaulting women in the dark. Julian convinces Randy to start engaging in risky behavior and play cruel pranks on her classmates and teachers. He dares her to stand on the edge of a cliff, gets her to close her eyes, and then scares her so badly that she almost falls. She puts a fake spider in the desk of an arachnophobic teacher and then laughs when the teacher passes out, and she posts a forged love note in the school hallway that almost results in a violent altercation between two of her classmates. When Alice expresses concern about Julian’s influence and Randy’s behavior, Randy shrugs it off and basically cuts Alice out of her life.

But who is Julian and where has he come from? He told Randy that he was helping his grandparents fix up the house next door, but she never sees him over there working and he never invites her to meet his grandparents. Alice gradually becomes convinced that Julian is just a figment of Randy’s imagination, a hallucination that gives Randy free reign to indulge her most irrational and destructive desires, and this seems to be a pretty plausible explanation, especially after Alice breaks into the house next door to see whether she can verify Julian’s story. Randy panics when Julian pushes Alice down the stairs, but when she goes to help her friend, Alice screams at Randy to stay away, screaming “HELP! HELP! RANDY DON’T TOUCH ME! … It was YOU! It was you all along. YOU PUSHED ME DOWN THE STAIRS!” (143, emphasis original).

Randy is devastated, terrified that she can no longer distinguish between fiction and reality. But things get even messier when it turns out that Alice’s hypothesis is only half true: Randy hasn’t been herself and she has been doing horrible things as a result of Julian’s influence, but Julian’s definitely a real guy, who escaped from a juvenile correctional facility and has been LIVING IN RANDY’S ATTIC CRAWLSPACE. He has been hiding in her house the whole time, watching her. When Randy flees to the attic crawlspace to try to get away from Julian, she finds all kinds of things that have mysteriously been going missing around the house: “There was an old coat, and a credit card with her name on it, and her telephone message pad … A blanket. And a pillow. Then her eye saw something in the corner and realized it was the cheerleading sweater she’d been missing” (153). The telephone pad has been missing since before Randy even met Julian, so this guy has been in her house for AWHILE. Julian pursues Randy up into the crawlspace and out onto the roof of the house, threatening to kill her, but in the end, he’s the one who ends up falling off the roof.

Julian lives and is taken back into custody, and Randy’s life goes back to normal(ish), as she patches things up with both Alice and Ted. Ted really wants to see himself as a hero, telling the girls that he showed up at the house at the tail-end of Randy and Julian’s confrontation because “I just had a feeling. Well—maybe I just wanted to see Randy” (159, emphasis original). But when he arrives, there’s not much for him to do: Julian has already fallen by the time Ted pulls into the driveway, and by the time he makes it inside the house, Randy has already crawled in from the roof and called 911. Ted’s astute thoughts on the whole ordeal are that “If I live to be a hundred, I’ll still say … wow. WOW” (160). (Okay, Ted might not be a catch, but doesn’t go around grabbing women or hiding in their walls). It has all been too weird and traumatic, however, and the restoration of normality doesn’t hold. Randy and her dad move and the person who buys their house also buys the house next door and tears them both down. Though the property is empty, “People avoided the place because whenever anyone passed, they felt as if someone was hiding there, watching them … and they hurried past as fear gripped their hearts” (163). It could be the memory now tied to the space, likely repeated as local gossip or an urban legend, or maybe Julian is back, watching and waiting. Like Randy herself, the reader is left wondering, unsure whether to trust their own instincts or perceptions.

In Stine’s The Boy Next Door, Scott Collins is a bit less mysterious, but just as dangerous. Scott and his parents move in next door to Crystal Thomas on Fear Street, and Scott immediately becomes the talk of Shadyside High School—at least with the girls. Crystal and her best friend Lynne Palmer have a not-so-friendly competition about who will get a date with him first; even Crystal’s shy sister Melinda is interested. But Scott doesn’t seem interested in dating anyone and while most of the girls just get annoyed and frustrated by Scott’s refusal to notice any of them, Melinda suggests that he may harbor a secret sadness, a trauma from which he is still recovering. This proves to be the case, as the girls learn that Scott’s last girlfriend died, which was part of the reason his family relocated to Shadyside. What Scott doesn’t tell them is that he’s the one who killed her.

In Smith’s The Boy Next Door, readers never really know why Julian does the things he does, but Stine includes several first-person sections in his book that reveal Scott’s thoughts and motivations, which are unsettling. As Scott remembers his dead girlfriend Dana, he thinks “I had no choice. Anyone would agree with me … When I first started going out with Dana, she seemed like such a nice girl. Such a sweetheart … [But] She started dressing in those short skirts. Wearing all that makeup. Acting so wild, so disgusting … Oh, Dana! That was no way to behave” (3). Dana transgressed Scott’s restrictive idea of “proper” femininity and as a result, she had to be killed. When his family moves to Shadyside, Scott figures if he just stays “far away from girls like [that]” (4), he’ll be just fine and he won’t have to kill again. Stine does give us some insight into Scott’s family life and it’s clear that his values have been passed down and reinforced by his parents, who are big proponents of “traditional” family dynamics, conservatism, and propriety. Scott’s dad gets American Family magazine, which heralds traditional family values, and when Lynne calls Scott, his mother reminds him over a very stiff, formal dinner that “It wouldn’t do if you got involved with a girl like that. You understand that, don’t you? That girl doesn’t know how to behave!” (75). In addition to this policing of sexuality and “proper” gender and relationship roles, propriety is the order of the day in the Collins house and Scott and his mother have another tense moment when he drops his fork, which “clattered against the side of my plate. Mom glanced up sharply … She didn’t have to say a word … I knew exactly what she was thinking. I almost scratched her best china!” (75). Scott’s parents have established clear and restrictive expectations for him, which he internalizes and strives to live up to. When he falls short of those expectations or encounters girls—like Dana, Crystal, and Lynne—who challenge those, his discomfort turns to rage and violence against those young women.

Given the double standard women face to be both alluring and unattainable, it’s unsurprising that the girls of Shadyside find themselves in a no-win situation: they wear their shortest skirts and spend a lot of time on their makeup in the hope of catching Scott’s eye, never suspecting that his gaze is predatory rather than appreciative. Lynne takes a chance and kisses Scott, so he murders her (though he manipulates the scene to make it look like a suicide, much like he made Dana’s death look like a tragic accident). Scott actually likes Melinda, who dresses modestly, doesn’t give much thought to her appearance, and would rather spend her evenings reading classic literature in the attic than going out to parties with Crystal and her friends. Crystal gives her sister a makeover in preparation for her date with Scott, who hates her new look and is ready to kill her too, before Melinda tells him it was all Crystal’s idea.

Scott comes over to the girls’ house following his date with Melinda, ready to reestablish his ideal status quo and get back the version of Melinda he wants. As he walks into their house with a knife in hand, he reassures Melinda and thinks “Of course I wouldn’t hurt Melinda in any way … She was so good. So well-behaved … But Crystal had to be punished. Crystal had to pay” (133). In his mind, he’s the one who gets to decide and mete out his own version of “justice,” having judged these girls on the basis of their appearance, dress, and behavior. But the situation is more complicated than he anticipates, because after Crystal’s makeover and now that the girls are dressed similarly in their at-home, casual clothes, Scott can’t tell them apart. Melinda and Crystal work together to trick him and (in an unsettling echo of Smith’s The Boy Next Door) attempt to flee to the attic for safety, which isn’t a great idea. Luckily, there’s a random (and convenient) hole in the attic floor and just as Scott is about to kill the sisters, he plummets through the hole to the hallway below and dies.

Crystal and Melinda have more of a happily ever after than Smith’s Randy: in the book’s final chapter, Stine highlights how the girls have changed. They are no longer diametrically opposed, with Crystal as the pretty but shallow party girl and Melinda the dowdy intellectual. Melinda has started wearing more fashionable clothes and a bit of makeup (though her approach to beauty is more subtle than her sister’s), while Crystal is trying to share in some of her sister’s interests, as the two girls get ready to watch Pride and Prejudice together … which only holds their attention until the new family pulls in next door and they happen to have a handsome teenage son.

In both Smith and Stine’s The Boy Next Door, the predictable domestic facade hides dark secrets and untold terror. While some of these horrors are figurative, like the damagingly repressive beliefs of Scott and his family, others are more disturbingly literal, like a dangerous criminal hiding in Randy’s wall and creeping around her house while she sleeps. The boy next door isn’t supposed to be dangerous, but when these girls find out that he is, no one believes them and even their own homes become unsafe.

Both Smith and Sinclair undermine the expected comfort of the “boy next door” trope and both of these young men are incredibly dangerous. What’s almost as dangerous, however, is the fact that no one believes these girls when they reach out for help. In the early chapters of Smith’s The Boy Next Door, Randy sees movement and light in the abandoned house next door and calls the police. The female officer is sympathetic to Randy’s fear but her male partner yells at Randy, berating her and accusing her of playing a “little prank” (17); when Randy and the female officer object, he shouts them both down and tells Randy not to call them back out there, which leaves her with little reassurance that she can turn to the police when things start to get unsettling and later, dangerous. Even Randy’s best friend Alice doubts Randy’s experiences, believing—and even briefly convincing Randy—that it’s all in Randy’s head. In Stine’s The Boy Next Door, Crystal begins to get suspicious of Scott after Lynne’s death and tries to warn Melinda that he may not be who he says he is, but Melinda defends him, dismissing Crystal’s concerns as jealousy that Scott chose Melinda over her (which, in all fairness, is partly true).

Smith and Stine’s versions of The Boy Next Door challenge the predictability and comfort such a figure usually offers, a disruption that reverberates out to the larger domestic sphere of the girls’ homes as well. In both books, the boy is a force of chaos that compromises the young women’s relationships, the choices they make, and their safety. And while it may be easy for the girls to keep a (potentially voyeuristic) eye on the boy next door, the terrifying inverse of that proximity is that he could always be watching too and sometimes, like in Sinclair’s book, even closer than she thinks.