I’ll kick this one off with a question that has likely passed through more minds than just my own: do you remember the very last time you spent the night at a childhood friend’s house?

The final Saturday night you stayed up until 4 am playing GTA, or building a blanket fort and getting shushed by their mom for giggling in the waterbed an hour later? The last morning you woke up smelling like said mom’s cigarette smoke and got sent home at 1:30 pm, grumpy and exhausted and dreading school the next day?

I may be getting oddly specific. The point is this: I don’t remember that final sleepover. Because of course, I did not know then that an era I had long taken for granted, a decade of whispered ghost stories and Doritos dust and fears confessed in the dark, had ended. Only in hindsight did I realize that a door had closed somewhere between my friend and me. We would never again share those little moments that had been a fundamental aspect of our lives. We would no longer be in each other’s lives at all, a thing once thought unfathomable.

A human life is short in the great scheme of things, but anyone will tell you that time seems to accelerate as you age. What, then, must it feel like to live for a thousand years? For Frieren, the eponymous elven heroine of Frieren: Beyond Journey’s End, a day must feel incredibly brief.

Even a decade-long journey, culminating in saving the world, could hardly feel noteworthy to an immortal mage. By the time Frieren travels with Himmel the hero, Eisen the warrior, and Heiter the priest to the northern lands to slay the demon king, she’s already old as dirt. She doubts anything on the journey will surprise her. When we are young, every new experience feels sharp and overwhelming. Our first time getting stung by a bee seems agonizing, but we may forget our last ones.

In the anime’s first episode, Frieren attends the funeral of the human hero Himmel, her former traveling companion. She overhears human attendees remark that her lack of reaction seems truly coldhearted. Later, at his gravesite, the permanence of Himmel’s death finally dawns on her. “Why didn’t I try to get to know him better?” she asks, sobbing.

That question pushes this whole gorgeous story forward.

Too Much, Too Late

Himmel’s death is far from the first or last loss Frieren has experienced, but it catalyzes her to start living again. She may not quite understand why, though to viewers it seems obvious. While journeying north with her new companions, Fern and Stark, Frieren claims that elves “lack romantic feelings and reproductive instincts.” Stoked as I am to embrace Frieren as another excellent example of ace/aro representation, I think it’s apparent that, in her way, Frieren fell in love with Himmel the Hero.

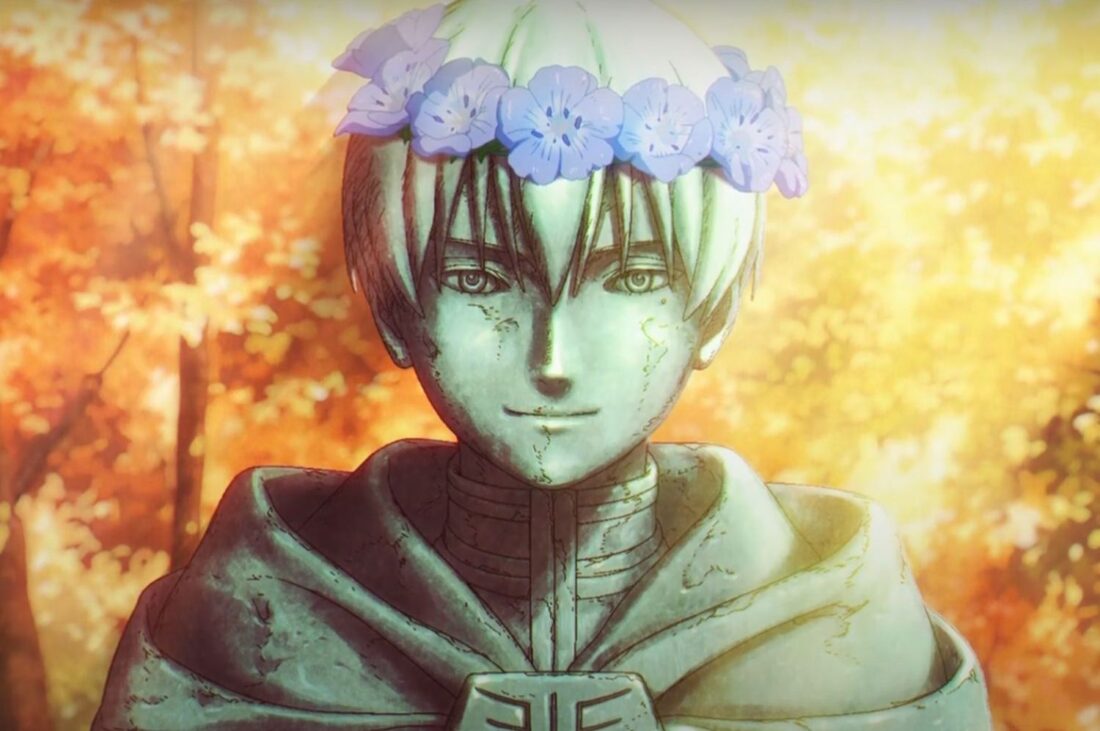

And who wouldn’t? Himmel is the sort of starry-eyed, truly good person whose real heroism lies in his tendency to help any person he comes across, be it a shepherd with an unruly herd or a village contending with a resident demon. Through Frieren’s recollections, we see Himmel as unusually charming and wise, despite his human faults. He can be vain and a bit too righteous, and he makes a few catastrophic decisions. He relishes adventure and cherishes sunrises. Every so often, he reveals his deep insecurities. “Helping people is the only way to be remembered,” he suggests, implying that his motives are not always selfless.

Across their ten-year journey, Frieren hardly responds to Himmel’s moments of profundity. Frieren is old and jaded and odd to boot, and feelings have never been her strong suit. Just as starlight sometimes reaches Earth millennia after the star’s demise, Frieren realizes the weight of Himmel’s presence in her life only in the years after his death. However blatant Himmel’s unique affection for her is to viewers, Frieren has yet to come to terms with it, even eighty years after she knew him.

When Frieren asks Himmel why he always poses for statues in the little villages they save, he tells her, “We aren’t a fairy tale. We really existed. But really… I pose for these statues so you won’t feel alone in the future.”

Himmel is always aware of his mortality, and how humble a role he must play in the history of the world. Simultaneously, because Himmel is deeply empathetic, he understands that Frieren’s feelings for him, however slow-moving, may be stronger than she realizes. But he does not presume he can remain a part of Frieren’s long life, however much he may admire her. It is almost impossible for him to confess.

Every episode of Beyond Journey’s End includes a caption that describes the setting as follows: (fantasy town or region), # of years after the death of Himmel the Hero. However many years Frieren may live, however long subsequent journeys will take, Himmel fundamentally changed her world and story for eternity.

What a bittersweet tragedy that he knew it and did not say it, and that she would only come to know it later.

Every Life is a Montage

There are many brilliant strokes that set Frieren apart, but chief among them is the genius of the pacing. From episode one onward, the audience experiences life at the same uneven tempo as Frieren herself. In the pilot, fifty years pass in two minutes as Frieren travels around the world indulging in her hobby of collecting spells. If she is taken aback when, returning from her travels, she finds her friends old and withered, the audience (however unsurprised) can empathize with her sense of displacement. We have seen seasons and years pass in a gloriously animated little montage.

This storytelling tactic of alternating between snapshot montages that cover years and years and real-time chronicling of single moments would seem clumsy in a poorly written novel. Frieren delivers these alternating bouts of pacing with superb care. The moments at which we pause and the moments passed over are always deliberately chosen. Frieren’s life accelerates when it is less remarkable and slows when events force the old mage to focus on the present.

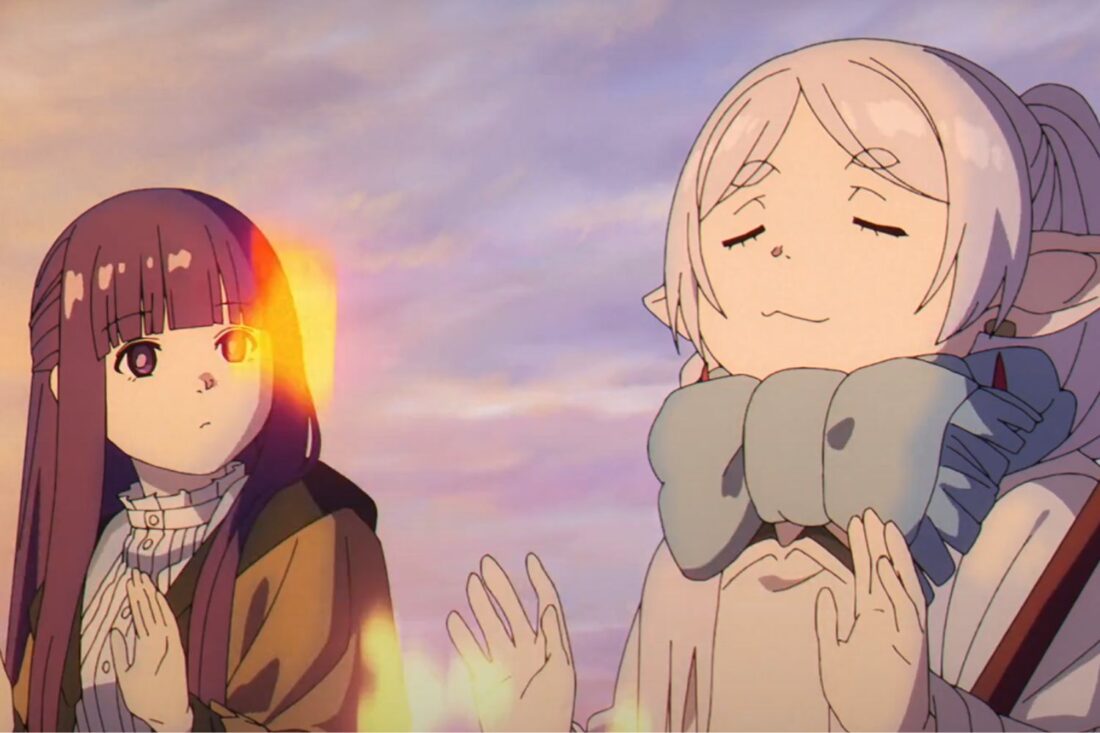

When Heiter, the priest Frieren and Himmel traveled with, asks Frieren to take on an orphan girl, Fern, as an apprentice, Frieren refuses but agrees to stay with them for a while to research a grimoire. Heiter knows Frieren will lose track of time, and under their combined care we see Fern grow from an angry child to a practical young mage in a single episode. By the time Heiter dies, Fern has long since become Frieren’s apprentice. She and Fern hit the road together, and Frieren has no choice, now, but to live life at a much more human pace. When Frieren shows worrying signs of hunting for a wildflower for three years straight, Fern puts her foot down.

As the story progresses, the montages become shorter and farther between. The show goes from chronicling years in minutes to stretching the events of a few hours over four different episodes. If this seems like a negative, it isn’t. Fern’s company forces Frieren to be present and react in real time to the needs of the mortals around her.

In one town, Fern insists Frieren get up early to see the sunrise. Frieren is not a morning person, and when Fern sits her in front of the horizon, at first she expresses confusion. “It’s just a sunrise like any other.” But then she sees the wonder on her apprentice’s face and understanding dawns. “I see. I wouldn’t have been able to see this sunrise if I’d been on my own.”

Initially, Frieren believes that the brevity of human life means their days are longer. But a day is still twenty-four hours, a week is still seven days. Just because Frieren’s life is long does not mean her time actually passes more quickly. The passage of time is more about perspective, about actively choosing to make the most of individual moments. Frieren is happy to waste her own time, but she’s uncomfortable wasting her student’s. She is far too great a teacher for that.

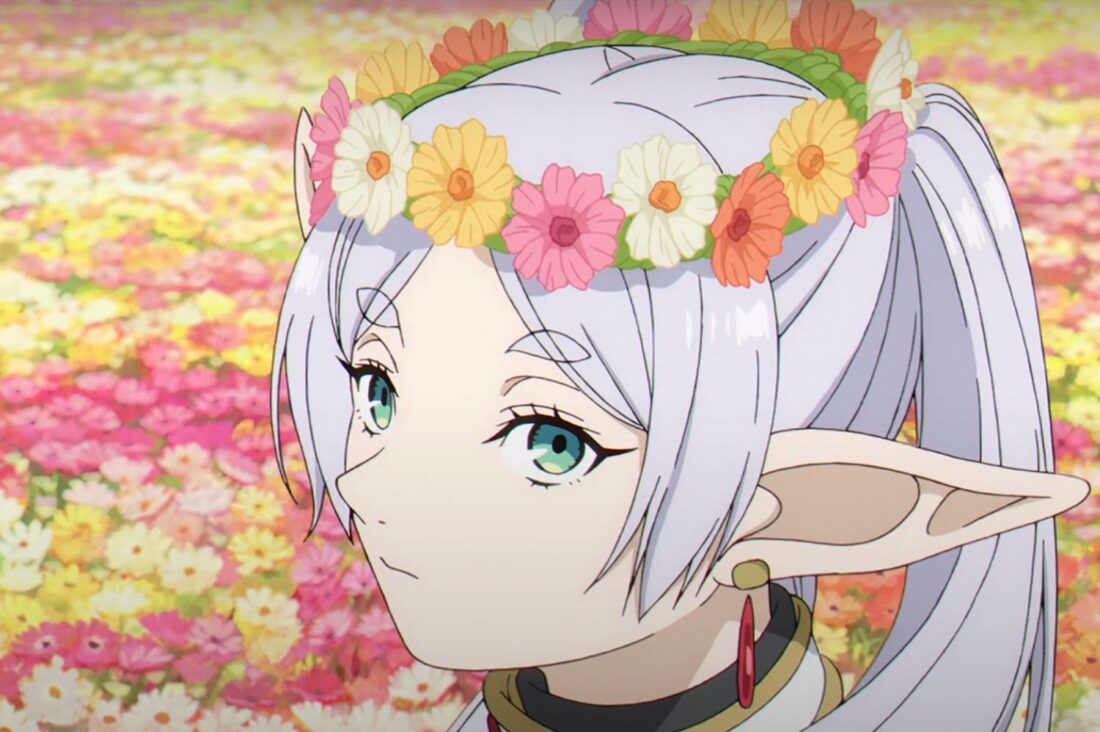

To Those Who Teach

I did not expect Frieren to be an ode to teachers, but it absolutely is. In her youth, Frieren was mentored by one of the greatest human mages of all time. Flamme, a sorceress who essentially invented humanity’s magic, never thought less of Frieren for being unambitious. She understood that trauma can impact people in different ways, and Frieren’s apparent lack of compassion need not be a failing. There is great power in being unassuming and quietly skilled, and Flamme also planted the seeds of caring in Frieren. Flamme loved magic and wanted it to be accessible to all people. She wanted the future to be a time of peace, and trusted that, however long it might take, her oddball elven student was the right person to make that future a reality.

When Frieren takes Fern on as an apprentice hundreds of years later, she is just as confident in her student. Nothing makes someone as objective as immortality, and Frieren is honest with Fern from the start. She sees that Fern, too, lacks purpose, especially after the demise of her caretaker. But that is no reason not to teach her. They ask each other whether they love magic and fail to answer with conviction. Frieren knows they might stumble into conviction as they travel.

Hers is a lesson in appreciation. Frieren is never sparing with her compliments. When she meets Stark, the young warrior who becomes the third member of her traveling party, he has deeply internalized the message that he is a worthless coward. He came from a village of warriors but fled as a boy and has never forgiven himself. He confides in Fern that even though he trained hard, he was never once praised by Eisen, his former master.

Frieren doesn’t know this and she does not care. She tells him to fight a dragon because she is certain he can do it despite his own doubts; Stark slays the dragon with ease. The very first thing she does is praise Stark for his efforts. “Well done. You exceeded my expectations.” It isn’t flattery; Frieren is far from deceptive (with one major demon-related caveat). It’s the truth, imparted to a young boy by an ancient creature.

Frieren is an excellent teacher not only because she is experienced and honest, but because she remains a good student. Despite her well-worn habits and flaws, she revises her previous beliefs when she learns new information. Even at a thousand years old, she is still willing to learn. We can all only hope to age so gracefully.

Humble Joys are Joys All the Same

“Frieren struggles to understand emotions,” the priest Heiter tells Fern, shortly before his death. “But there’s no teacher better than her.”

Though this might be interpreted as a unique elven trait, the other elves we meet in the series, though few, do seem more passionate than Frieren. It is possible that Frieren has always been an odd duck, even among her own people. But there are elements of Frieren’s social dysfunction that feel like textbook depression. Being disaffected rather than sad or angry is a coping mechanism, as many of us know. In the very earliest flashback into Frieren’s life, she is the sole survivor of an attack on her village, and she failed to save her people. We do not know who she was before that; perhaps she was the same, or perhaps she was more compassionate. It doesn’t matter. Frieren can only be who she is now.

Flamme encouraged Frieren to value the humblest of spells and smallest of treasures. Flamme knew that joy, however fleeting, is still joy. For the long swathes of Frieren’s life when she lived in isolation in what may have been a centuries-long slump after Flamme’s death, Frieren’s hobby of collecting folk spells, magical herbs, and grimoires was enough to give her long life purpose. It is this sense of wonder that keeps her living, that keeps her warm, that keeps her amusing.

Himmel cemented this vital lesson. During their ten-year journey, he never took fun for granted. In one recollection, Frieren remembers learning a spell for making shaved ice, much to Heiter’s delight. The dwarf, Eisen, asks Himmel whether spending time on such things during their important quest isn’t a waste of time. Himmel has a different mindset. “I’d rather enjoy a ridiculous and fun journey that we can laugh about when it’s over.” Just because a journey is long doesn’t mean it must be miserable.

At a thousand years old, Frieren frequently gets swallowed by Mimics, monsters that imitate treasure chests. Because what about that one percent chance that this time, the Mimic is an actual treasure chest? She never learns her lesson, and she keeps opening those chests, and Fern keeps pulling her out of them. The appeal of a potential discovery is just too powerful. At some point, Frieren’s little magic-collecting hobby became something akin to a calling.

Across twenty-eight episodes, Frieren becomes a little more expressive, prone to genuine smiles and true exclamations of affection for others. She begins, again, to have fun. It’s as though traveling with Fern and Stark allows her to emerge, at last, from another long winter.

Wisdom Takes Empathy and Practice, Not Time

We could all learn from this tired, clumsy, all-powerful elf to be more gracious with our compliments. From Himmel, we learn that helping others is the best way to matter in the world. From Stark, we learn that being afraid does not mean being weak. From Fern, we learn that practicality can solve most problems and that living without purpose does not mean a purpose will never be found.

And from the series? We are reassured that anime as a medium can still be wildly ambitious, powerful, and beautiful. On the whole, Frieren: Beyond Journey’s End is the very definition of bittersweet. It is affecting, philosophical, charming, clever, and features a protagonist that is among the most brilliantly characterized I have ever seen. It also feels especially timely here in Japan, a nation grappling with an aging population.

I teach pudgy-faced toddlers in some of my ESL classes, and last week after we all sang the Alphabet song, one little boy was inconsolable when it was time for him to put his maracas away. He screamed as though I had burned him, pounding the carpet with his furious fists, and clutched at the maracas as his mother handed them to me. Clearly, he had rarely experienced such devastating loss. What a monstrous thing, to lose not one, but two maracas, stolen by the devilish sensei!

Yesterday, when we sang the put-away song, the same boy held on only briefly, his sadness fleeting, and put the maracas away by himself.

How nice it is to watch another series that lives up to all the hype. It seems like an excellent time for fantasy anime! Next time, I’ll be writing a retrospective on one of my favorite series of all time, Natsume’s Book of Friends, to celebrate the arrival of its seventh season this October. After that, we’ll be getting into some spooky anime in time for Halloween. A piece on Junji Ito? A yokai appreciation bit? A Mushishi revisit? An investigation into body horror in anime? Feel free to leave comments and suggestions!

In this article:

Up Next: