Interior Chinatown—styled as Int. Chinatown at the opening of each episode—is a 10-episode adaptation of Charles Yu’s amazing, National Book Award-winning 2020 novel. (Here’s my review of the book, and an interview I got to do with Yu back in 2021.) I am ecstatic to say that the show builds on the book’s premise in really cool ways, takes the characters in surprising new directions, and adds even more depth and layers to the side characters—even Turner and Green! It’s also even funnier than the book (and the book was really, really funny) and, I think, even more emotionally raw at some points.

The show was written by Charles Yu, Eva Anderson, Matt Okumura, Tiffany So & Saba Saghafi, Naiem Bouier, Keiko Green, Lauren Otero, Alex Russell, and Greg Cabrera, with Yu writing the pilot and finale. The episodes were directed by Taika Waititi, Ben Sinclair, Jaffar Mahmood, Alice Wu, Stephanie Laing, Pete Chatmon, John Lee, and Anu Vali. Waititi’s episode was properly flashy and hyperkinetic, but each director brought unique visual flair—the whole show looks great. I especially enjoyed how the tone went from moody and noir-y in Wu’s “Chinatown Expert,” to a bleached out desert palette in Chatmon’s “Detective.”

The performances are uniformly fantastic. Jimmy O. Yang has to embody a bunch of different stereotypes and archetypes over the course of the show including but not limited to: “waiter in the background of an SVU episode,” “Kung Fu Guy,” “Tech Nerd,” “Detective on a Procedural (Urban),” Detective on a Procedural (Rural),” and “bland-but-hot star of an upscale ad”—and all of them are pitch perfect. Which would be hard enough, but he’s also Willis underneath all of them, aching to get out and be his full self. While everyone is great, Yang really has to carry the show. It’s Willis’ journey that carries us through the episodes, grounds all the genre shifts, and adds a jolt of reality to the surrealism. And throughout, whether it’s his resignation as more and more bags of garbage appear out of nowhere in the back of the Golden Palace in the pilot, his tamped-down growing panic in “Ad Man,” the long, revelatory scene in “Translator”—Willis is real.

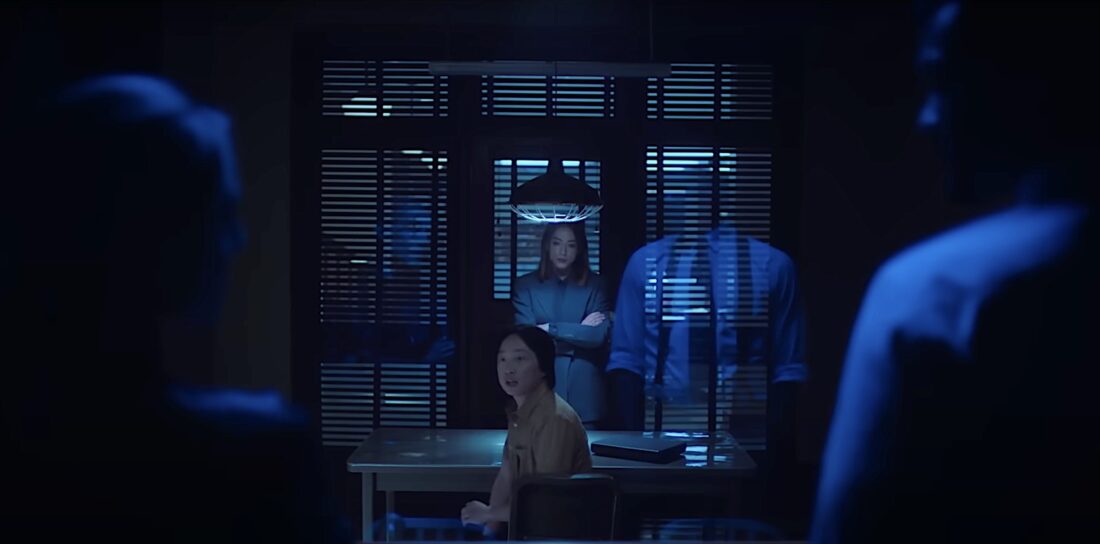

There isn’t a weak spot in the cast, from Annie Chang as Audrey Chan, the go-getter with the overbearing mom, Chau Long as Carl, the hapless Golden Palace busboy, Archie Kao as Uncle Wong, the Golden Palace’s owner and the fixture in the neighborhood who tries to keep everyone else as safe and stable as possible, and Chris Pang as Older Brother, who has to convey years of history in only a few scenes. The two halves of Black & White are Lisa Gilroy as Sarah Green and Sullivan Jones as Miles Turner, lead detectives for the Impossible Crimes Unit. In Interior Chinatown‘s blurry reality, they believe they are real cops solving real impossible crimes, but there are also sometimes credits and a theme song that frames Green and Turner as TV stars—even though they don’t seem aware of this. Green is the stone-faced quippy one, who has to prove herself to the boys by being a hard-ass, and Turner is the secret nerd with a tragic past. And of course, over the course of the show, we see more layers from Green, and Turner starts to question the nature of reality in an arc that somehow balances humor with existential terror.

Ronny Chieng is fucking hilarious as Fatty Choi. (“Are you trying to teach me a lesson in personal responsibility??? Don’t do that, it’s gross! I don’t wanna hear that shit!”) His arc is great, probably my favorite part of the show, but I’ll get into that in a spoiler section in a minute. Chloe Bennett is amazing as, again, a real human trying to live up to an archetype (“ridiculously-hot-guest-lead-detective-on-a-procedural-who-has-special-knowledge-of-this-week’s-case-but-has-to-win-over-the-two-actual-leads”) who gradually falls the hell apart over the course of the series as more of her actual personality and backstory are revealed. As another character on Black & White she has to walk a fine line between Sarah Green’s solid belief that she’s really a cop solving real Impossible Crimes, and Miles Turner’s growing suspicions about their reality. When she’s away from her role with the police, she has other problems to navigate: Are she and Willis friends, partners, or something else? Will the people of Chinatown ever accept her, a multiracial outsider? Will she have to keep proving that she belongs? One of the great strengths of the show—and Bennett’s performance—is that all of those elements hit just as hard as the fun, meta one where she’s been brought in as the “Chinatown Expert” on a TV show that is also a real police force. Kind of.

Willis’ parents, Lily and Joe, are played by Diana Lin and Tzi Ma. (Fun side note, the audiobook of Interior Chinatown was narrated by Tzi Ma’s Man in the High Castle costar Joel de la Fuente!) In the book the Wus get a long middle section that follows them as the emigrate to the US, meet, fall in love, and have a glamorous youth before…well, before America chews them up and spits them out. It’s a fantastic way to structure the book, because we meet them initially as depressed, disappointed, almost unknowable elders through Willis’ eyes. By rewinding and dropping us into their perspectives decades earlier, Yu is able to bring them to life as themselves, while also giving us more perspectives on the ways the American Dream can eat people. To be honest, I was dreading that the show would do the same thing, that suddenly we’d get a whole episode of Lily and Joe that would pull us out of the threads we were in. But the show instead takes their story and keeps it in the present. We watch as Lily tries to make a fresh start, process her grief for her older son, and throw herself into a new career, while Joe tries to figure out who he is without his old role as the Sifu of a Kung Fu school. It’s their arc, the most “realistic” one, that holds the heart of the show and grounds it most in our reality.

And having just said that Ronny Chieng’s arc was my favorite, I may need to immediately backtrack to give special attention to Archie Kao as Uncle Wong. In most shows, his role would be that of hard-ass boss who is simply an obstacle to his employees. Instead he gradually becomes more and more of a real, living person—a person working against impossible odds to try to keep his community safe. He does thankless work with grace and compassion, and, aside from Willis himself, I think he’s the character I’ve thought of most over the days since I finished the show.

The adaptation presents itself as a mystery, and most of the individual arcs loop and twist around each other as some characters (Lana Lee, Miles Turner, Willis himself) start to realize there are uncanny things afoot in Chinatown, while others (Sarah Green, Fatty Choi, the Wus) are focused on their day-to-day struggles and hardships. By the end it feels like at least three different shows are playing out simultaneously—in a good way.

The book takes a different turn, where Willis meets a lovely woman named Karen, marries, has a kid, moves to the suburbs, and becomes Kung Fu Dad for a while… until Turner and Green track them down, because Willis stole Turner’s car. This leads into a court transcript of the trial against Willis, and a reveal of what actually happened to Older Brother, and the court case leads back into the TV show which leads back into Willis being a dad and trying to work stuff out with his ex, and trying to have a relationship with his dad just as his dad, his daughter’s grandfather, rather than as “Sifu.” The blurring between reality and fantasy works extremely well, because, in a way, all of the television and film references become the roles people play in life—specifically the roles Asian-Americans feel trapped in by U.S. culture. A point that’s made repeatedly is that an “Asian-American face” is still, in the 21st Century, not seen as simply an “American” face: “That’s the dream of blending in. A dream of going from Generic Asian Man to just plain Generic Man.”

Working with the format of a novel, Yu is able to give his characters monologues, to describe action as though it’s stage direction, to roll along with a hilarious script until he needs to drop his readers into a scene of Willis watching his father play with his daughter, Phoebe, and make them cry. The book also includes lists of anti-Asian U.S. laws, starting from 1859, and culminating in 1924’s Federal Immigration Act, which set a quota on the number of immigrants allowed into the country—or, more accurately, set quotas on where immigrants could come from. It completely banned immigrants from Asia. And it stood until the Immigration and Nationality Act of (checks notes) 1965???

Nineteen-sixty-fucking-five??????

Great, America, that’s just great. Can’t wait to see what you do next, buddy.

The show doesn’t dig into that, choosing instead to focus on pop culture cliches before digging into the emotions under its storylines. Obviously the adaptation is able to satirize TV much more directly than the book could. There are the perfect Law & Order dun duns, the banger of an opening theme, the way the light cools to a steely blue every time Green & Turner stride onto a crime scene, before it slides back to warm natural light as they move on to the next case. At the season’s midpoint, Int. Chinatown turns into a more direct parody of two different procedurals: the creepy rural noir and the dockside sub-tropical noir, and does hilarious stuff with both before returning to its L&O: SVU SOP.

The show is also able to be even more meta than the book was, as it finds ways to show us Willis’ fractured state of mind. This is be best explored in the episode “Ad Guy,” where Willis’ insecurities play out through a series of advertisements that he’s starring in because he’s… a successful detective? But that doesn’t make much sense, does it? Why would a successful detective suddenly star in a series of high-end ads? And why have a sycophantic assistant running alongside him with coffee, and anticipating his every need? Why is the show suddenly a musical?

Okay, so about Fatty Choi’s arc. When Willis bails to help Lana Lee’s investigation, Fatty is stuck waiting tables. He’s never had to speak with the customers, he’s terrified of them, and then pretty much immediately furious when one of them orders ginger chicken without the ginger. The next time a white hipster couple comes in and has no idea what to order, he loses it and yells at them. And of course, being a particular type of white hipster, they’re ecstatic. They have been Called Out By An Authentic Member Of Another Culture, and they see it as part of the experience. Within a few days, there are lines of white hipsters out the door, all desperate for an uncomfortable encounter with the “Mean Waiter”—the now famous Fatty Choi. This was my favorite arc because, well, I saw like four different versions of myself in that line. I’m big enough to admit it, and I’d go to the Golden Palace right now if it existed in this timeline. The next time Willis checks in, the restaurant is bustling, and Fatty is, of course, still furious. “People are ordering stuff I didn’t even know we had! Like, what the fuck is crab rangoon???”

It’s been a while since I had to pause a show so I could laugh.

One of the strengths of the book was that all the meta fun made the emotions land harder. The gap between the book’s shifting structure—sometimes a cop procedural script, sometimes a glossy law drama, sometimes an early ’80s Kung Fu movie—and the very real struggles of the characters, I think, made their emotional lives vibrant in a way they wouldn’t have been in a more traditional Multi-Generational Epic Literary Novel. Not that I’m knocking those! There are lots of classics in that subgenre. But I thought Interior Chinatown was special precisely because every few pages it kicked down the walls it had just built and became something else.

The show does that even more.

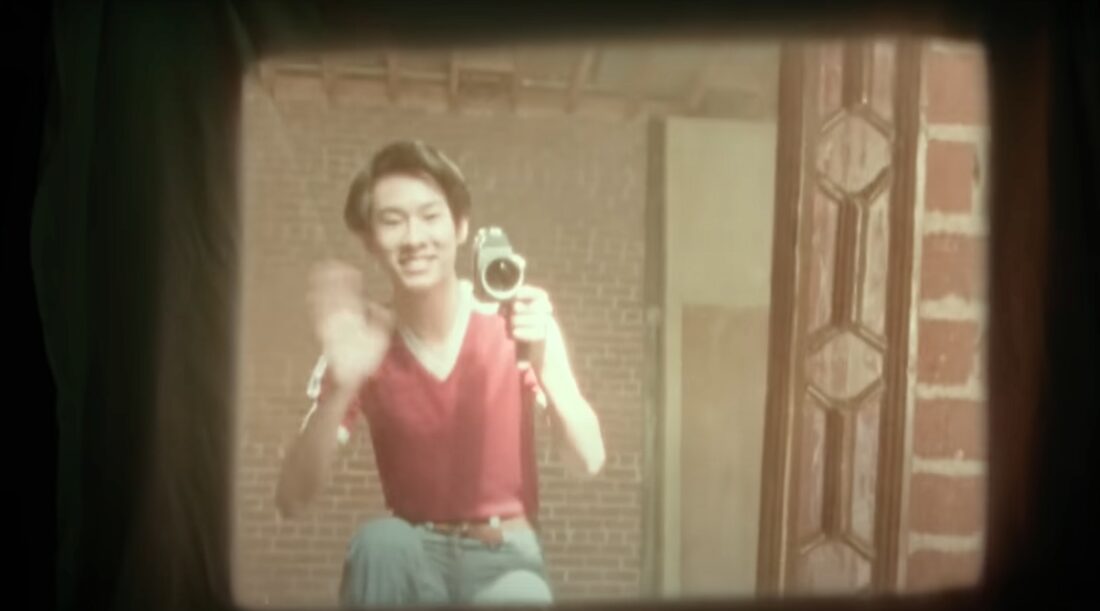

The details add to a perfect blurry reality that never settles into one era. Older Brother’s plot on Black & White is timestamped as 1984, and young adult Fatty lives in oversized Michael Jordan t-shirts, and most of his scenes are soundtracked to ’90s hip hop. However, everyone (both “on the show” and “off the show”) uses flip phones that no one had yet in 1996, the detectives drive enormous cars that seem to have rolled in from the late ’70s, the precinct’s tech setup seems much more recent than 1996, and the ubiquity of a (vaguely sinister) hard seltzer called Deep Water implies that the show is set right about now.

My only caveat with the show is that the ending fell a little flat—but then, again, when you’re creating this kind of high-wire maximalist plate-spinning act, it’s extremely difficult to come up with a resolution that will satisfy every plate. The book also had a couple of different endings before landing on a moment of overwhelming emotion, and then turning to a page of dry historical fact to sent the reader back into the world with a tangle of competing reactions—which worked perfectly as a reading experience. Here, the writers give the several of the plots good emotional resolutions, and throw one final gag out that kind of wraps things up—but because the show hinted toward an even larger, universe-shattering conspiracy, it can’t help but feel a little too neat. If there’s a second season, I will be ecstatic to go further into this world Charles Yu and his writers created.

Having said that, though, Interior Chinatown is fun and hilarious, and even made my dried out little husk of a heart ache a few times. It shows what a team of creative people can do when they’re given great source material, but they’re also willing to kick a lot of it through a window and run in cool new directions.