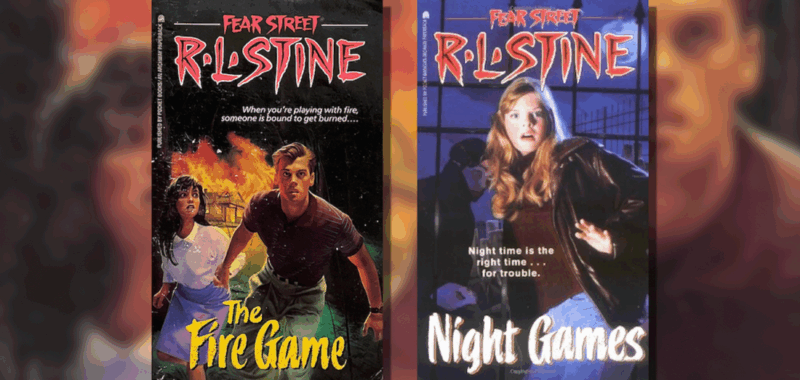

As the old saying goes, it’s all fun and games until somebody gets hurt. In ‘90s teen horror, the games are almost always dangerous, which is definitely the case in R.L. Stine’s Fear Street books The Fire Game (1991) and Night Games (1996). These games are risky, the stakes are high, and never mind getting hurt—there’s a better than even chance that somebody’s going to wind up dead.

In both The Fire Game and Night Games, groups of Shadyside teens walk on the wild side, setting fires around town in The Fire Game and doing all sorts of destructive things in Night Games, including breaking into and vandalizing the home of one of their teachers. While the characters know they’re making bad choices and that what they’re doing is wrong, they give into peer pressure and go along with the larger group. Aside from this groupthink, they are also seduced by the power and control these actions afford them. As Diane Browne, the protagonist and first-person narrator of Night Games reflects, part of the allure is “Freedom. That’s what it was. An exciting kind of freedom that made our skin tingle, made our senses more alert, made our hearts pound a little faster” (55). Their late-night adventures are a way to escape the control of their parents, teachers, and other adults who influence their lives, with Diane noting that “When you think about it, we don’t have much freedom during the day … There is always someone around to tell us where we have to go and what we have to do. Always someone to say ‘Go to school. Do your homework. Help your brother. Do your chores. Go to the store. Go to bed’” (56). Diane, her boyfriend Lenny, and their friends Cassie and Jordan don’t have difficult lives, but it is easy for them to feel like their days are regimented and beyond their control, as they live up to the responsibilities and expectations of the adults around them. The Night Games are an escape hatch, a Dionysian revelry and “After midnight, roaming the silent sidewalks and yards of Shadyside, we were in charge … The world belonged to us” (56, emphasis original).

The same is true with The Fire Game: though the first fire the teens set is an accident, they soon realize how much power they can wield. Two of the boys, Nick and Max, are playing around with lighters in the Shadyside High library as they tell their friends Jill, Andrea, and Diane (a different Diane than in Night Games) about a movie they watched the night before called The Torch, with a heroic figure “who can make fire come out of the tips of his fingers. Like a human flamethrower” (6). They enjoy goofing around and mimicking this supernatural power, but when Nick sets a folder on fire, Diane panics, screaming “Now you’ve done it!” (8) as she runs from the room. Diane has a phobia about fire and the others dismiss her response as an overreaction, extinguish the folder, and toss it into the wastebasket on their way out, but when the fire alarm goes off during their next class, they realize there must have still been some live embers. The school is evacuated and the fire is put out without any substantial damage, but they’ve seen the impact they can have with just a quick flick of a lighter, and that power quickly becomes intoxicating. A few days later, they decide they’d like to get out of school early, so Max sets a fire in the boys’ bathroom, which quickly turns into more than they bargained for when it hits a container of cleaning solution next to the wastebasket and the fire becomes an explosion … but they do get the afternoon off from school. They soon take their game off school grounds, setting fire to a rundown shed in the cemetery and later, someone sets fire to an abandoned house on Fear Street. Just like Diane and her friends in Night Games, they get a thrill from this destruction, both in the fires themselves and in not getting caught.

The core groups of characters in The Fire Game and Night Games are generally well-behaved and rule-abiding teenagers—or at least they have been until now. In both cases, an outsider shows up in Shadyside, exerting a bad influence that leads them down these collective, destructive paths. While these new guys in town are outsiders, however, they are not strangers: in The Fire Game, Gabe is the newcomer, but he and Diane grew up together and knew one another before she and her family moved to Shadyside, and in Night Games, Spencer was actually part of their friend group up until last winter when he mysteriously disappeared (when they’re all back together, he tells them that he and his family went to go live with his ill grandmother across the country). While the teens in The Fire Game are initially horrified by their accidental wastebasket fire, Gabe is soon egging them on, challenging each of them and telling them “it takes guts to set a fire deliberately” (16). In Night Games, the friends encounter Spencer climbing out of his bedroom window one night and he invites them to come along with him, telling them that “I have adventures … Some nights it’s hard to sleep. My head feels so crowded. So I sneak out for some Night Games. Quiet little adventures … in the dark” (11). He looks in people’s windows and he bangs on the window of a parked car, pretending to be a police officer and terrifying the two teens who are making out inside. When Spencer finds out that Lenny has had trouble with one of their teachers, Mr. Crowell, he turns their energies to terrorizing Crowell and vandalizing his house. Again, Diane knows that this is a bad idea but she reflects that there’s just something about Spencer: “he could make you follow him with just a smile or a word … He just seemed so … confident … As if he knew exactly what he was doing. As if he knew exactly what he wanted” (56). Gabe and Spencer have a bad influence on the other Shadyside teens of The Fire Game and Night Games, though once they’ve been seduced out of their comfort zones, most of them really enjoy the chance to lean into their previously untapped destructive potential.

Inevitably, things go too far and the “games” have horrifying and deadly consequences. In The Fire Game, Jill is headed to study with Nick and Gabe when she sees them leaving Nick’s house and heading to Fear Street. She follows them and eventually finds them fleeing an abandoned house that then goes up in flames. She doesn’t confront them but on that night’s evening news report, she learns that a homeless man was found on the porch of the house, killed as a result of the fire. The Night Games have deadly consequences as well–when the teens break into Mr. Crowell’s house to vandalize it, they find him dead inside. While they didn’t kill him, the news report following the discovery of his body speculates that he was literally frightened to death, suffering from a heart attack when his house was broken into. (After they find Mr. Crowell’s dead body, the poor guy pretty much becomes a non-entity in the story. They worry about evidence that would place them at the scene, but don’t seem to feel any remorse for how they’ve been harassing him. He doesn’t seem to have any friends or family—his body was found by his housekeeper—and the police don’t seem all that invested in figuring out what happened. He’s a mean teacher, he dies somewhat mysteriously, and after a perfunctory school assembly to recognize his passing, he just … disappears). When their “games” turn deadly, things abruptly shift from “fun” to criminal, and their own lives are on the line. It doesn’t take much for the teens to turn on one another: in The Fire Game, Jill accuses Nick and Gabe of setting the fire, which they deny, while in Night Games, Diane suspects Lenny of killing Mr. Crowell, and when they start getting threatening messages that implies someone knows what they did, they all suspect and accuse one another.

In both cases, the truth ends up being darker—and stranger—than fiction, as the catalysts behind characters’ destructive motivations come to light. In The Fire Game, Diane has a phobia of fire and is the most vocal about the game being a bad idea, while Gabe is constantly challenging the friends to set more (and bigger) fires. It turns out that Diane has good reason to be afraid of fires: she was nearly killed when her grandmother’s kerosene heater exploded and she was badly burned, an accident that has left her covered with “hideous scars” (139) that she has concealed with long sleeves and an unwillingness to undress in front of others in the locker room or at slumber parties, always retreating to a private stall or bathroom to change. Diane credits Gabe with saving her life because while she was recovering in the hospital, he would come to visit her, bring her homework, and keep her company. Diane loves Gabe, telling Jill “He gave me a reason to go on. A reason to want to fight the pain and live … He is my true soulmate. He gave me life” (140). Gabe doesn’t feel the same way about Diane, but instead of realizing that they may not be a good match for one another, Diane has settled into a pattern of self-loathing, certain that Gabe can never love her because of her injuries, which she sees as disfigurements. When Jill starts dating Gabe, Diane’s only recourse is to make sure Jill feels the same pain that she has, and Diane tricks Jill into spending a weekend with her at her parents’ cabin in the Fear Street woods, where she attacks her and tries to burn her face with a blowtorch before Gabe crashes in to the rescue. Diane’s the one who set the abandoned house on fire, and the one who has had the most to win—and lose—in the fire game. At the end of the book, Diane finally finds herself in Gabe’s arms as he embraces her to simultaneously comfort and restrain her, reassuring her that “The fire game is over. It’s over for good” (145). What will happen to Diane next is uncertain, but this is apparently the first time anyone has realized the psychological trauma she has carried since her accident, and hopefully she’ll get the help she needs to begin to heal.

The truth of Night Games is more … unconventional. There are a couple of flashback interludes throughout the book that take readers back to the previous winter, which was the last time the friends hung out with Spencer. They were spending a snowy weekend at Spencer’s uncle’s cabin and tensions were running high: Lenny and Diane were arguing and Spencer figured it was an ideal time to let Diane know how much he liked her, so he kissed her when they walked out to the woodpile to fetch more logs for the fire. Lenny didn’t like it, punched Spencer in the face, and then spent the rest of the weekend being a jerk to Spencer (interestingly, even though Diane is the first-person narrator for the majority of the book, we never learn what she thought or how she felt about this kiss). This culminates in a snowball fight that turns nasty: Spencer pelts Lenny and Jordan with ice balls, Lenny buries Spencer in the snow, and the rest of the teens head back to Shadyside. While it was intended as a joke—another one of those ill-fated “games”—Spencer can’t free himself from the snow and he suffocates and dies there. This seems like it would be pretty big news in a small town, or that at least Spencer’s parents might want to talk to some of the kids their son spent his last moments with, but apparently not. Spencer never turned back up in Shadyside after that weekend at the cabin and the rest of them just … figured that was no big deal? Nothing to worry about. They don’t make any attempt to reach out to him to see how he’s doing, make sure he’s okay, or apologize, and they’re not plagued by guilt or even mild concern about how they treated him. When he shows up again after nearly a year, it never seems to occur to them that there might be any tension or that he might not be all that happy to see them.

The deep, dark secret of Night Games is that when Diane and her friends have been sneaking out and wreaking havoc on Shadyside in the middle of the night, they’ve been following a ghost. Spencer’s the one who scared Mr. Crowell to death, and then he fakes his own death to lure the others into a trap when they come to find him. As they’re gathered in Spencer’s abandoned house, trying to figure out what to do, he suddenly “float[ed] off the floor. He spun around in the air. Hovered about two feet off the floor. His long white hair floated around his head like silver-white cobwebs … He spread his arms wide and his mouth opened. An ugly black hole. He let out a ghoulish, bone-chilling laugh” (142). Spencer is undead, angry, and fixated on making Diane and her friends pay for his death, first by framing them for Mr. Crowell’s death and then planning to kill at least some of them. When Spencer tells the others that they killed him, they seem genuinely surprised and horrified, with Diane wondering “Did we do something terrible—and not realize it?” (143). In the cosmology of Night Games, Spencer is able to maintain a corporeal form by channeling his anger, telling Diane “My hatred kept me here … It kept me here long enough to pay you back. Long enough to scare you to death!” (143-144) as he strangles her. Since it’s Spencer’s hatred that keeps him tethered to the world, the friends’ only recourse is to counter that hatred with love (apparently), and Diane, Lenny, Cassie, and Jordan surround Spencer, telling him “We like you” and “We missed you so much” and “You’re our friend, and we love you” (147). This may be an odd defense, it works and Spencer disappears, literally melting away into a “wet, blue puddle on the dark floor … And then the puddle vanished, too” (148). And just like that, their problem is solved: they don’t have to bear any responsibility for Spencer’s death or their vandalism of Mr. Crowell’s house, and they can shrug off their destructive behavior with “it was the ghost’s idea” and go back to their regular Shadyside lives … except for Diane, who Spencer killed, but she immediately became a ghost herself and maintained her physical form, and NO ONE NOTICED. This is understandably traumatic and Spencer’s rage seems to have been passed on to Diane, who watches her friends and thinks “All three of them stood and watched me die … They didn’t move. They didn’t help … Should I tell them that I’m dead now? Or should I wait—and play some games of my own?” (149). It seems the games aren’t over just yet.

In The Fire Game and Night Games, these teens’ “games” quickly get out of hand and turn destructive. Some of their actions are relatively harmless pranks, like when Spencer scares the couple who are making out in a parked car, but most of them are dangerous and criminal. They set fires and break into a teacher’s house, seeing it all as just a “game,” a source of entertainment and a thrilling rush of power they don’t have elsewhere in their lives. They have no sense of the consequences of their actions or how they hurt other people: in The Fire Game, Gabe is all about setting fires and doesn’t seem to even consider how this might be triggering for Diane, who nearly died in one. In Night Games, the kids’ snowball fight goes too far and they don’t even realize that Spencer is dead as a result of their actions. Later, as the group runs through Shadyside playing their Night Games, they view Mr. Crowell is a depersonalized villain and victim, seeing his terror as a source of entertainment. These “games” have consequences that go well beyond anything the teens anticipated. They’re playing for keeps, and nobody wins.