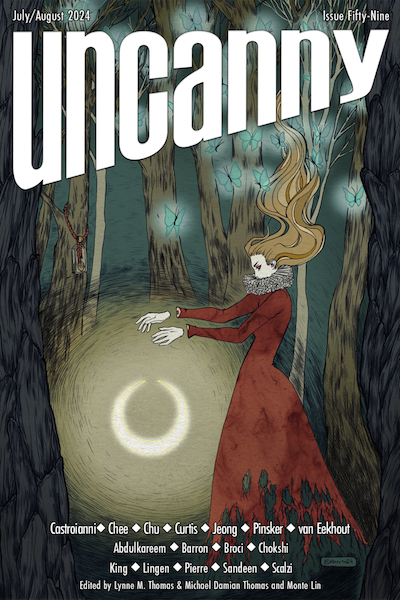

Welcome back to Reading the Weird, in which we get girl cooties all over weird fiction, cosmic horror, and Lovecraftiana—from its historical roots through its most recent branches. This week, we cover Megan Chee’s “The Worms That Ate the Universe,” first published in July 2024 in Uncanny Magazine. Spoilers ahead!

Summary

On a barren, sunless world live the worms. They don’t think, and they feel nothing but the hunger that drives them to their sole endeavor: eating. They gnaw away at their planet from surface rock through molten core. In addition to material, though, they consume space—distance. If you tried to walk a straight line on the surface, you would find yourself taking detours to the far side of the planet.

Meanwhile, elsewhere in the universe, faster-than-light travel remains a dream. A dream, that is, until the worms evolve, and then FTL travel becomes a nightmare. One worm escapes the dwindling substance of their home—it gulps atmosphere and just keeps going, engulfing the other planets in their system. Most of its fellows devour each other. A few follow the explorer. Eating. Multiplying. For eons, the worms munch their way through lifeless expanses of space, with only a few advanced civilizations aware of their baleful progress. Still, myths spring up. On desert Sutera, nomads tell of a strange oasis and impossible lake filled with ravenous monsters. One pair of exiled lovers leap into the lake and manage to swim to an island on which they can love each other safely, surrounded by horrors.

Eventually the worms tunnel into occupied space and become fact rather than legend. Some peoples search for ways to close the wormholes, to no avail. Others, like the warlike folk of Grirri, see opportunity. The Grirri hordes plunge through a wormhole, only to be crushed under the paws of the giant felines who rule the other end.

Some planets die in a millisecond, gulped by particularly large worms. Others perish to swarms of smaller worms. Millions of societies condense into one fractured civilization. It’s an age of “chaos, of confusion, of spectacular strangeness,” In cities built on “the fragments of disparate worlds,” citizens wear protective suits, drive armored vehicles, shop in marketplaces that boast “dizzying array[s] of oddities and curiosities,” while their children play in the low-gravity zones between planetary shards.

As “the remnants of civilization stagger in discordant harmony toward the end of all things,” the worms eat on. Finally, only two bits of intelligent life remain: a generation ship carrying the last best minds of Earth, and a young woman living alone in a house on the last sliver of her planet. From her bedroom window, the woman can look through one of the generation ship portholes into the quarters of a young officer. The women share no common language, but they wave, gaze, smile and laugh and play out little charades.

In the end, with the worms converging on ship and house, the pair press palms to their respective windows. The young woman mouths what can only be “a wish for something that never was.” When their remnant worlds are gone, the worms turn on each other. They tangle into a writhing ball “squeezed into the last speck of the universe,” and there’s—

“A great bite, a huge chomp—

“A squelch, a crunch—

“And that’s it.”

What’s Cyclopean: Chomp. Squelch. Crunch.

The Degenerate Dutch: The warriors of Grirri believe the wormholes are proof of their interplanetary manifest destiny. Unfortunately, the first species they encounter offworld are giant cats. Never cross the cats.

Weirdbuilding: Wormholes are a longstanding trope of science fiction. An actual biological source for those wormholes not so much, though it isn’t unheard of.

Ruthanna’s Commentary

Cosmic horror can be minds and dimensions beyond human ken—Cthulhu’s incomprehensible moral guidance or whole ecologies swirling around us unseen. Or Azathoth, “mindless” because what it has instead is so vast and all-encompassing as to make mind-ness irrelevant. But cosmic horror can also be implacably simple—hunger, say, combined with being further up the food chain than we apex omnivores would like to believe possible. Maybe much further.

Chee’s wormhole worms fall into the latter category. They’re not only hungry, but capable of eating anything: molten planetary cores, atmospheric gases, the fabric of spacetime itself. Nothing eats them, though they’ll eat each other if nothing else is available. After a while, that becomes an extremely existential definition of “nothing.”

It could be a one-note idea/joke story about “what if wormholes are really created by worms,” but the answer to that what-if—taken seriously—is practically symphonic. It’s an overture of loneliness, with all the universe’s sapients imprisoned by the speed of light. The worms become legend, and a source of possibility and togetherness for a select few—the folklore they inspire is about star-crossed lovers finding safe havens, more than the surrounding monsters. Then a crescendo of connection: conquest and crossover and the ultimate cosmopolitan society. The universe gets smaller, and the worms keep eating… and then finally we’re back down to loneliness again, and a pair of women stretching the last possibility of connection across barriers—before barriers (and reality itself) go crunch.

We talk about modern communication technologies making the world smaller, and fostering connection. And it’s also true that sometimes they seem voracious. They consume the very things they enable. Don’t you just hate a good metaphor?

That symphonic middle reminds me of Ng Yi-Sheng’s delightfully cacophonous “Xingzhou,” and I could easily believe that they take place in the same universe, with Yi-Sheng zooming in on one of many wormhole-enabled epics. But nothing so lively can last, and the epic is all past tense: What was it like to live in Xingzhou, the Continent of Stars? That story doesn’t give much insight into the later period from whence that question is asked, but it might easily be one of Lovecraft’s fever-dream apocalypses—which aren’t too far off from the worm-riddled universe here as the symphony winds down.

The horror is that not only the universe’s fate, but its entire arc, is shaped by simple, unsated hunger. The worms themselves get no pleasure from their feast. They don’t notice differences in taste and texture between lunar schist and glorious interplanetary capitol. They aren’t part of a well-balanced ecosystem. They don’t create intricate philosophies around their biological necessities. They aren’t even cute when they sleep, because they don’t sleep. But the saving grace is that the sapients who live with wormy inevitability make meaningful lives from the worm’s mindless consumption. They get pleasure and philosophy and joy in difference that they wouldn’t have found in a universe without the worms.

John M. Ford’s “Against Entropy,” a gorgeous sonnet on mortality and memory, also starts with hungry worms as the source of loss. I have the poem’s last line in a calligraphic print on my side table. Really I could just quote the whole thing as sufficient commentary on Chee’s story. What do we do about the fact that “The universe winds down. That’s how it’s made.”? We tell stories. We make connections. We do it again, iterating in the hopes that something is preserved for as long as possible. We hope to be remembered in the Archives.

For as long as we have a choice, we do not look away from each other.

Anne’s Commentary

Worms! They’re everybody’s worst nightmare! The screenwriters got it wrong in Raiders of the Lost Ark—when the real Indiana Jones gazed down into a pit full of squirming, crawling, writhing beasts, he didn’t groan, “Why’d it have to be snakes” but “Why’d it have to be WORMS.”

You do know Indiana Jones was real, right? Anyhow, he developed a pathological fear of worms following a boyhood fishing accident. In fact, he had all the worm-dread pathologies: helminthophobia, the fear of being infested with parasitic worms; vermiphobia, the fear of being infested by worms of any species; and scoleciphobia, the fear of worms in general. It probably would have killed him to read Megan Chee’s story, so luckily he died before it was published. One of his numerous enemies would surely have sent him a link, without trigger warnings and after hacking the title to “The Giant Fluffy Kittens that Ate the Universe.” Fair enough, as Chee does mention such creatures.

It has been written that “In the beginning was the Worm.” I’m not on board with this, because it’s established ultrametaphysics that in the eternal beginning (which therefore never began, begins or will ever begin) was Azathoth. Besides, as Chee explains it, there was an awful lot of universe already begun before the worms began gnawing through their home world. In the context of her eschatology, it would be more accurate to write: “In the Beginning of the End was the Worm.” Specifically, this Beginning began when the species evolved to use its distance eating ability to traverse the vasty expanses of outer space via, what else, wormholes. Those wily worms, but then, isn’t survival the greatest driver of innovation, and for the worms, isn’t survival the satisfaction of their limitless hunger?

The worms haven’t yet reached our insignificant sliver of the universe (or I wouldn’t be writing this), but rumor of their coming and ultimate conquest must have visited Chee in some premonitory dream. Cassandra-like, she tries to warn us!

Uh, no. Warning could do no good, for when the worms come to dinner, there will be no barring them from the table, only futile attempts to keep them out on the front lawn while we pack our vittles into generation RVs and sneak out the back way. The back way is still the universe, and the universe must be eaten. It’s the Way of the Worm.

As before, as now, as in the future, some among us will more or less hazily perceive our world’s wormy doom. Here are just a few examples of how such sensitives have sublimated their perceptions into legend and art.

Variations on a World-Serpent or Ouroboros occur in many cultures and philosophies. The snake or dragon eating its own tail (thus forming a circle) can be a symbol of eternal cycles, life to death to rebirth, destruction to renewal. Or those notions could be optimistic interpretations of the last universe-eating worm, which having devoured all matter and space and its fellows must now devour itself, oops, the end.

Edgar Allen Poe dreamt (or at least wrote a poem) about a “tragedy, ‘Man,’ and its hero the Conqueror Worm.” The Worm is “a blood-red thing” bearing “vermin fangs/In human gore imbued.” Sounds like a good description of Chee’s ever-ravenous omnivores.

Bram Stoker produced The Lair of the White Worm, which features a giant white serpent that preys on every living thing it can find, but not apparently on inorganic matter or space itself, which leaves it way behind Chee’s worms on the indiscriminate gluttony scale.

In his Dreamlands stories, Lovecraft mentions a vast wormlike creature called a Dhole, which riddles whole planets with its tunneling. One theory about how it travels is that the Dhole can swim through space when magically summoned; another is that it can force its way through the interdimensional fabric of dreams to jump planet to planet.

Brian Lumley wrote about subterranean horrors called Cthonians: part worm, part squid, all trouble. They, too, had the nasty habit of “drilling” such extensive tunnels and cavities that they destabilized infested land masses.

Finally, there’s the traditional ditty often called “The Hearse Song.” It has many variants. I learned this one in grade school, not from the teachers but from certain classmates who spent many hours in the cloakroom thinking about their sins.

Don’t ever laugh when a hearse goes by,

For you may be the next to die.

They wrap you up in a linen sheet,

And throw you down about six feet deep.

The next three days are all alike,

And then the worms begin to bite.

The worms crawl in, the worms crawl out,

They poke their knuckles right up your snout.

Goodbye, Jimmy! [or the name of whatever kid you were tormenting at the moment.]

If T. S. Eliot had written about “Hollow Planets” instead of “Hollow Men,” he might have ended the poem: This is the way the worlds end/Not with a bang but a squish.

Or as Chee puts it with equal eloquence, regarding the ultimate triumph of the worms:

“A great bite, a huge chomp—

“A squelch, a crunch—

“And that’s it.”

Unless, of course, the worms in their self-destruction pop out into another of Azathoth’s countless bubble-universes and start chowing down on a new smorgasbord.

Next week, Louis definitely doesn’t follow good advice in Chapter 22 of Pet Sematary