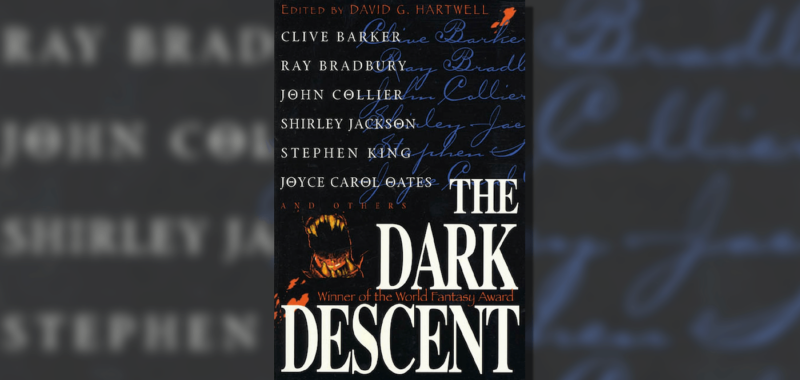

Welcome back to Dissecting The Dark Descent, where we lovingly delve into the guts of David Hartwell’s seminal 1987 anthology story by story, and in the process, explore the underpinnings of a genre we all love. For an in-depth introduction, here’s the intro post.

“What Was It?” is something of an outlier for The Dark Descent. While Hartwell might classify it as a horror story, the bright tone, slapstick comedy, and general lack of menace would identify it as a comic fantasy, albeit one with a few gothic overtones. It’s a story about a group of blowhards and horror fans who take a practical and rational approach to what could be a terrifying situation, shining a light on a seemingly supernatural threat that, as with most horror stories, resists or lacks definition. In spite of its antithetical premise, “What Was It?” has just as much reason to exist in The Dark Descent as its more unnerving cohorts—it’s a comic work that demonstrates what horror is by offering a twist on genre conventions and readers’ expectations.

The inhabitants of the old boarding house on Twenty-Sixth Street are an eccentric group, a mixture of intellectuals and artists who all share a passion for one thing: horror stories. Inspired by the stories of the many ghosts said to be occupying the infamously haunted former mansion due to the numerous ghost stories within its walls, they’ve taken up residence in the hopes of experiencing the subject of their favorite books for themselves. Unfortunately, all the rumored hauntings turn out to be a bunch of bunk, largely based in the occasional drunken rumors from the house butler. That is, until one unusual night, Harry, the narrator, is awoken by a mysterious, invisible, and apparently homicidal presence attacking him. Have the boarders gotten more than they bargained for, or are their dreams of experiencing supernatural phenomena finally coming true? And what is the thing that attacked the narrator, anyway?

From the jump, there’s a sense of fun to “What Was It?” While Harry manages to keep it together for a page or two by opening the story in a style similar to many of the gothic horrors we’ve covered, his description of the entire boarding house fighting over a book of ghost stories or how he and his neighbor smoke opium together, then force each other to think happy thoughts to avoid a bad trip, quickly give the game away. If stories like “Clara Militch,” “The Yellow Wallpaper,” and “The Beckoning Fair One” are about people going insane due to isolation, the jocularity of “What Was It?” points to the inverse situation—a whole group of people staying sane together because they’ve found each other and support each other. Just the fact that all these weirdos moved in together at the merest suggestion that the boarding house on Twenty-Sixth might be haunted, then stayed there even after they found out it wasn’t, speaks to a larger and more supportive network than most horror protagonists can rely on. When the narrator grapples with his invisible assailant, there are people running into his room almost instantly to help.

Harry manages to fend off and pin his attacker, and is joined seconds later by his opium-smoking buddy Hammond, which speaks to a deeper connection than maybe the droll narrator might suggest. Here, again, O’Brien inverts conventions now familiar to readers of this column and readers of The Dark Descent, in that the hero straight-up grabs the thing strangling him and fights with it. He manages to subdue it through sheer brute force, despite being bitten by “needle-sharp teeth” and feeling its sinewy arms wrapped around his neck—only to realize that the thing is completely invisible, at which point he cries out in terror. In Harry and Hammond’s earlier discussion while smoking opium, they’d been trying to pinpoint what they considered the “greatest element of terror,” and concluded that stumbling upon a corpse in the dark, while terrifying, is not the true terror they believe they’re looking for. There’s a sense that Hammond and Harry engage in their nightly rituals and love of the macabre partially because they’re trying to wrestle with their own traumas and the idea of undefined terrors in reality, a diagnosis often leveled at horror fans. All of this is quickly defused when the physical realities of the situation become clear and graspable: horror, in O’Brien’s eyes, is about things outside the rational context, things the rational mind can find no explanation for.

The moment the slapstick of Harry wrestling with an invisible demon, yelling at Hammond to touch it, and Hammond doing so, then immediately deciding they need to send for a doctor and an artist come into play, that rational context reasserts itself. The absurd becomes funny rather than terrifying. The indefinable becomes defined, growing ever more so when they chloroform the invisible creature, chain it down, and make a plaster cast of its body. While it’s an unnerving situation to discover that their boarding house menaced by a homicidal invisible imp (in a nice reference, the monster is described similarly to the creature from The Nightmare by Henry Fuseli), the imp is bound by physical laws, can be fought, can be knocked out and contained.

This absurdity of the terror in the dark transforming into a curiosity in the light instantly changes the horror to outright comedy. The threat is no less threatening (well, if they hadn’t chained it up and chloroformed it, anyway), but the story ultimately becomes a strange blend of comic fantasy—even the tidy way everything’s wrapped up fits more with a comic fantasy with slapstick humor than with horror, especially (as Hartwell categorizes it) “the fantastic,” where the horror often comes from an undefined or unexplained force. The heroes keep the plaster cast on display, neglect the monster until it dies from starvation or unknown reasons, and finally bury it, in a scene even Harry remarks on as absurd, dumping the invisible body into a four-foot hole in the garden where he and Hammond meet to smoke opium. In this way, the familiar, expected ending of a horror story—nebulous, uneasy, and characterized with more questions than there are answers—is also inverted.

While that’s the case, O’Brien’s conclusion to “What Was It?” offers one more sly poke at his protagonists and human nature. With the threat vanquished and most (though not all) of the mysteries solved, the offhand way Harry reports the death of the creature and subsequent burial indicates a waning of interest—with the mystery solved, there’s no more reason to pay attention to it, which most likely results in the neglect and death of the creature at its center. The heroes need that terror, that undefined space, those unexplained things to give meaning and spice to their lives. Harry and Hammond and their friends can live in the space where things are explained, but the unexplained gives their lives meaning, even in the controlled manner of horror stories and local ghost stories. It’s the same way people need experiences with the larger world outside their own mundane context to bring meaning and (for lack of a better term) life to their existence—maybe not invisible gremlins, but the point still stands.

For all he might invert and deconstruct the horror premise in “What Was It?”, this is the statement Fitz-James O’Brien ends on. In writing a horror story where all the horror elements are defused and turned on their heads, he doesn’t merely define horror is but demonstrate why horror—and indeed fantastic fiction—are essential to living a full life. Horror is an odd genre where people encounter strange and unfamiliar elements outside of their normal context, things which are often indefinable by all they know, but in cases where the mystery is solved and the fantastic turns to the mundane, the disruptive element loses any cachet or value it might hold and is promptly discarded. As much as we’re driven to solve and reveal, human beings still need their mysteries and dark spaces. Especially the ones we swear don’t exist.

And now to turn it over to you: Does the invisible imp in “What Was It?” stand in for the undefined in horror? Does a comic fantasy story belong in The Dark Descent? And—in a bit of a twist—what was the first story that made you believe in ghosts?

Please join us in two weeks for another look at Shirley Jackson’s work with “The Beautiful Stranger.”